After the chilliness of the morning all but evaporated, I found myself climbing into a cavernous riverbed. Behind me, lay our matatu, a local minibus, which we’d teetered in the past couple hours down rural, rocky paths, taking the occasional detour through acacia bushes. Once I reach the riverbed, I unprofessionally scramble to the other side to avoid wet socks, and begin the traditional introductions to everyone in the community that has gathered for the occasion. We exchange handshakes and hugs; I’m overwhelmed with the joy and gratitude of the women, and after a couple of minutes, we pray before beginning the interviews.

I spent my summer in the back of a matatu driving down precarious roads, hiking barefoot through sandy waterways, and sitting on sandbanks with Swahili and Kamba translators to interview local communities. With the guidance of Agroforestry Professor Wayne Teel from James Madison University, we conducted research for the Utooni Development Organization (UDO) in Machakos County, Kenya. As we recorded data from sand dams, collected water samples, and spoke with local communities, we cataloged information from the sand dams for Utooni and reported water sanitation data to the communities. My work in Machakos was made possible by the SNF Paideia Dialogue Funding, and it has inspired me to continue researching the effect of water availability on female economic empowerment. My experience was not only academically enriching but also deeply moving, as I witnessed firsthand the transformative power of simple yet innovative solutions to water scarcity and contamination.

To begin, let me explain the role of a sand dam. A sand dam is a reinforced concrete wall built across a seasonal river or stream. During rainy seasons, water flows over the dam, depositing sand behind it. This accumulated sand acts like a giant sponge, storing water within its particles and keeping it cool and protected from evaporation. The sand also naturally filters the water, making it cleaner and safer for use.

The Utooni Development Organization, founded in 1978 by local farmers in the Machakos region, has been at the forefront of implementing this technology. Faced with challenges of water scarcity, environmental degradation, and food insecurity, these visionary farmers sought sustainable solutions to improve their community’s resilience. UDO identified sand dams as a particularly suitable solution for the region due to their low cost, effectiveness, and ability to improve water availability sustainably.

My day-to-day research was a mix of scientific analysis and community engagement. Each morning, after a breakfast of mandazi, mayai, chai, and an hour of Swahili lessons, our research team would split into groups and head out to visit the sand dams. Our goal was to assess 25 Utooni sand dams over several weeks.

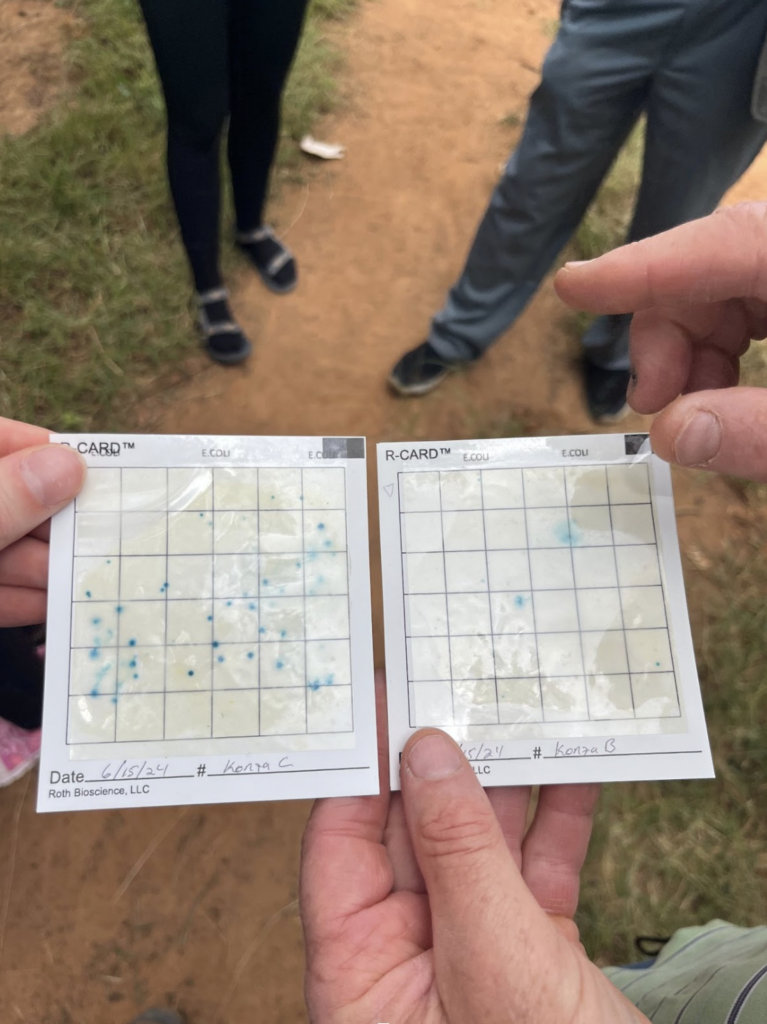

At each dam, we conducted a series of scientific water tests. Using portable meters, we measured water clarity, electrical conductivity, salinity, total dissolved solids, and temperature at various points along the dams. We collected water samples from pre-existing and self-dug scoop holes, as well as from any water pumps present. These samples were later tested for E. coli using a portable 24-hour incubator back at our hotel. This testing was crucial to ensure the safety of the water sources for the communities.

Another critical aspect of our research involved measuring the physical dimensions of the dams. Armed with measuring tapes, notebooks, and Google Maps, we meticulously recorded the length, width, and height of each structure. This data would later help us estimate the water storage capacity of the dams using rough calculations and GIS software mapping.

However, the most impactful part of our research was our interactions with the local communities, particularly the conversations we had with the mamas (the reverential title of the older women within these communities). These women, who traditionally bear the responsibility of water collection, shared stories that brought the importance of our work into sharp focus.

Before the sand dams were built, many mamas spoke of the hardships they faced. They described long, arduous journeys to fetch water, often walking for hours under the scorching sun. One mama recounted how she used to make the four-hour round trip to the nearest well, carrying heavy containers of water on her back and the family mule. This daily struggle meant less time for other activities, including caring for their families and engaging in income-generating work.

The mamas also shared distressing stories of having to choose between using their limited resources for water or for their children’s education. During dry seasons, some families are forced to take their children out of school to help with water collection or to use school fees to buy food from the market instead of growing their own crops, due to lack of water for irrigation.

The contrast in their lives after the construction of sand dams was striking. With a reliable water source nearby, the mamas spoke of newfound time for other activities. They could now engage in small-scale agriculture, growing a variety of crops like mangoes, bananas, papayas, sweet potatoes, avocados, oranges, and napier grass – produce that was unimaginable in this arid region just a few years ago. The increased food security and potential for income generation had a ripple effect on the entire community’s well-being.

Throughout our research, the four pillars of the SNF Paideia Program – dialogue, citizenship, service, and wellness – were evident in every aspect of our work.

Dialogue was at the heart of our research methodology. Our conversations with the mamas and other community members provided invaluable insights into the real-world impact of the sand dams. These discussions went beyond mere data collection; they were a mutual exchange of knowledge and experiences that enriched our understanding and ensured our research remained grounded in the community’s needs.

The spirit of citizenship was palpable in the communities we visited. The construction and maintenance of sand dams required collective effort and cooperation. It was inspiring to see how these communities came together, transcending individual differences, to build and maintain these vital structures. Their sense of shared responsibility and mutual support was a powerful example of civic engagement in action.

Our research itself was an act of service. By providing valuable data and insights, we aimed to contribute to the improvement of sand dams and, by extension, the lives of community members. Ultimately, our data will aid Utooni in future grant applications to build more sand dams, swelling their impact in the region. We were inspired by the selfless service of the mamas, who dedicated themselves not only to their families but to the broader community, ensuring everyone had access to water.

Lastly, the impact on wellness was profound. The sand dams improved physical health by providing access to cleaner water and reducing the physical strain of water collection. They enhanced economic wellness by enabling better agricultural practices and increasing food security. The time saved from not having to fetch water could be used for other productive activities, further contributing to overall well-being.

As I reflect on this experience, I am filled with gratitude for the opportunity to contribute to such meaningful work. The resilience, generosity, and wisdom of the communities we worked with have left an indelible mark on me. I want to extend my heartfelt thanks to the SNF Paideia Program for supporting this research. Their commitment to fostering citizenship, dialogue, service, and wellness has not only shaped my approach to this project but has also deepened my understanding of sustainable development and community-driven solutions.

This summer in Machakos County has reinforced my belief in the power of simple, innovative solutions to address complex challenges. The sand dams of Utooni are more than just water storage structures; they are beacons of hope, catalysts for community empowerment, and testament to the transformative power of collective action. As I move forward in my academic and professional journey, I carry with me the lessons learned from the mamas of Machakos – lessons of resilience, community, and the profound impact of access to clean water.

All images courtesy of Griffin Pitt.