From lab to community

According to Mecky Pohlschröder, Professor of Biology and lead instructor, the vision for the class was to connect STEM research with a community component so that students who typically work in a laboratory setting develop an understanding of how their research both influences and should be influenced by underserved communities and populations. Pohlschröder explained, “The first part of the course involved workshops on developing skills and confidence to access scientific research, literature, and the professional scientific community, components often overlooked in introductory STEM courses. The second part, the community connection piece, was completely new this semester.” The students had to develop a relationship with external stakeholders, identify the needs of the community, and develop their research project in response to the input they received from the non-Penn collaborators. “At the beginning, it was not clear to the students why the community piece was important,” according to Pohlschröder, “But by the end of the course, the students were excited because the experience showed them that their expertise as a biologist can lead to positive change; Penn values their contributions and the communities they come from; and community can be an important contributor to the research process.” To facilitate the course development and the addition of a community component, Professor Pohlschröder worked with Jean-Marie Kouassi, who led the community partnership piece, and Wil Prall, graduate student in biology, co-developer of the research and laboratory component of the course alongside Dr. Pohlschröder, and TA for the course this spring.

Design of the innovative class

The 20 students in the course were all first-generation, limited income college students, preselected from the Penn First Exposure to Research in Biological Science (PennFERBS) program. PennFERBS launched in 2020 as a collaborative effort between program director Mecky Pohlschröder and Wil Prall of the School of Arts & Sciences, Kristen Lynch of the Perelman School of Medicine, Keisha Johnson of the Pre-Freshmen Program (PFP), Pamela Edwards of the Penn College Achievement Program (PennCAP), and Bruce Lenthall from the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL), according to an article published in Penn Today. The article states: “The program focuses on promoting students from groups underrepresented in STEM, enhancing peer social support, and training students to take on leadership roles.” Students from PennFERBS came into this new SNF Paideia course with an affinity with the communities they were partnering with. As Jean-Marie explained, the students in FERBS are sensitive to power dynamics between Penn and the surrounding communities and were able to approach the communities as valued stakeholders. “It was a side-by-side approach, garnering input from both the community and students at Penn, to create a partnership to solve a problem that is crucial within the community,” he said. In this way, the community was teaching the students, Prall added. “Courses in the STEM fields are always taught in a very hierarchical way, with a PhD scientist teaching students through rote learning. In our course, the students went from sitting in a chemistry lecture to being in the driver’s seat, leading projects and listening to people with real-world experience of the issues at stake.”

Research that has a community impact

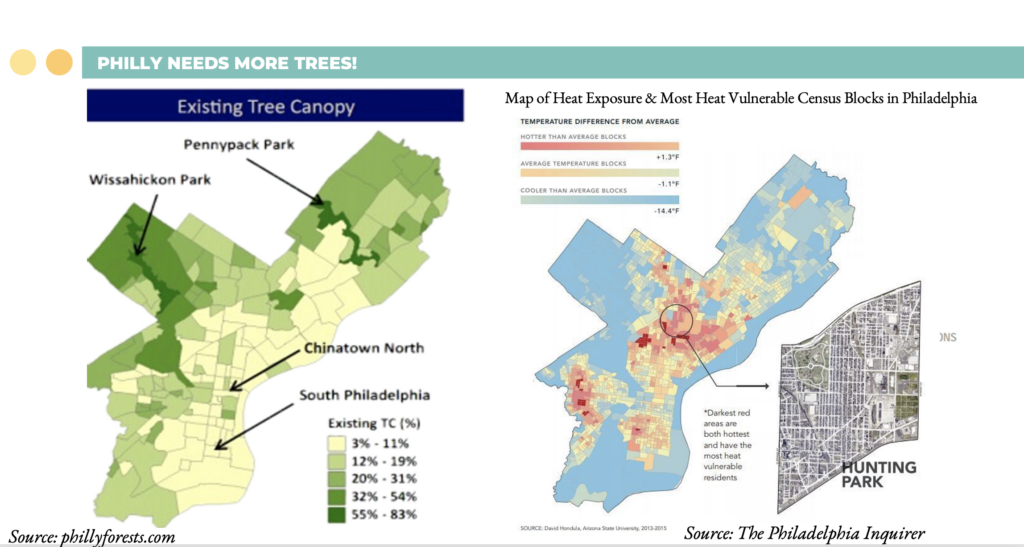

The specific projects were based on work the students had done during the fall semester, according to Pohlschröder. “Seven students were already in plant labs,” she said. “We encourage the students to think about how what they are doing in a plant lab, for example, translate into a community project?” Out of this group, an interest in studying the impact of urbanization, the diminishing tree canopy, and the effects on the community in Philadelphia emerged. Ummayh Siddiqua, C’25, is a potential biology major with a minor in chemistry and is on the pre-med track. Because of her previous work in the plant biology lab, Ummayh was assigned to the tree canopy group. At the beginning of the semester, she thought the project would be like other environmental work she had done but soon realized the project was more than advocating for biodiversity in Philadelphia. “When we started to do the research, it became obvious quickly that at its heart, we were looking at the social implications accompanying an environmental concern. The communities in South-West and West Philadelphia are facing consequences beyond increased temperatures due to a lack of tree canopy. They are seeing, for instance, an increased rate of hospitalization for childhood asthma, a long-term effect of poor air quality correlated with lack of plant life necessary to absorb carbon-dioxide.” This was an important turning point for her group, to realize the research they were doing had a social perspective with humanitarian consequences.

Although the plant lab experience informed their approach, the concept for the research wasn’t fully realized until the students met with the community partners. Prall elaborated, “A shell of an idea was developed by the students and then, working with Jean-Marie and the audiences most likely to benefit from the research, the students identified the needs of the community and developed the research in collaboration with the community stakeholders.” Anisa Robinson, C’25, one of the students in the tree canopy group who is studying biology with a possible concentration in ecology or evolutionary biology learned the importance of listening to community partners before implementing a plan. As she explained, “We worked directly with organizations already familiar with the issues happening on the ground, how to resolve them, and the politics involved. FERBS taught me how important it is to apply the research that I am doing in the classroom and in the lab to real world issues and experiences.” Ummayh reiterated the importance of partnering with community members, “We realized it wasn’t about teaching the community, it was also about educating ourselves and to experience the learning along-side our partners.” By listening to experts who had previously worked in the neighborhoods and creating an experiential learning component for the youth, Penn students were able to design an interaction that created excitement and inspiration around biodiversity for the teens and their parents.

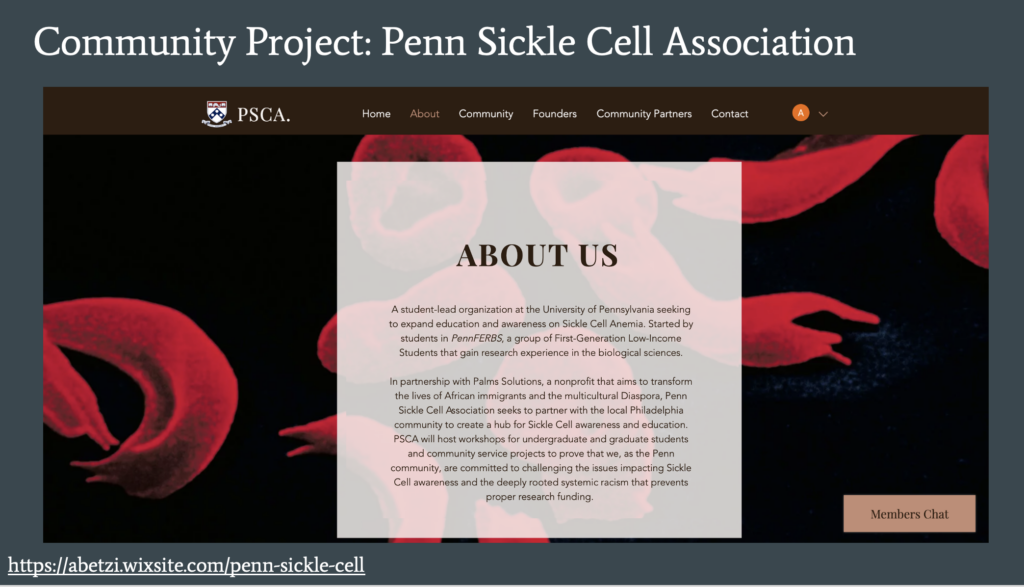

Other projects included a look at Racism and Sickle Cell Anemia and the Neurobiological impacts of COVID-19. The Sickle Cell group included Francisca Kwakye, C’25, a Penn student originally from Ghana who had Sickle Cell until the age of nine when she received a bone marrow transplant. “Growing up with Sickle Cell, I endured many pain crises, I wasn’t able to walk to school, my sister had to carry me on her back, I had stroke symptoms, I couldn’t play with my friends because I would end up needing oxygen. I was placed in the Sickle Cell group because of my prior lab research with cells and I felt like this was a great opportunity for me to share my experience with my classmates and meet a few people who are working with Sickle Cell patients.” The community component of the group included conversations with Zemoria Brandon, Administrator/ Social Worker of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America, Philadelphia/Delaware Valley Chapter, and Dr. Ike Okwerekwu, a pharmacist who has Sickle Cell Disease to learn more about the social implications of lack of understanding and misdiagnosis. Ms. Brandon spoke with the class about her work as an advocate for clients and families who are struggling with social ramifications of Sickle Cell Disease. “A student that’s been placed on academic probation because of missing school from being hospitalized; a parent who has lost their job because they had to take time off to care for a family member; someone who applied for social security disability but was denied; a client in the ER who is in pain but is not given their pain medication because they are misdiagnosed as drug seeking. These are a few examples of the breadth of interventions we offer for those suffering from Sickle Cell.” The gap that exists between the experience of Sickle Cell Disease and the understanding by medical professionals begins in medical school, she explains. “There is very little information, maybe a couple of paragraphs, about Sickle Cell in medical school curriculum. And doctors are taught to err on the side of caution when prescribing medication. When you have a patient of color showing up in the ER and they know their pain protocol, and they say I take 100mg of this medication, the medical personnel are alarmed that this is opioid drug seeking behavior.” Ms. Brandon and Dr. Okwerekwu also presented on how institutional racism exacerbates the problem. “Sickle Cell effects African Americans in the greatest number,” she explained. “The Hispanic population is the next group. Patients avoid going to the ER because of the discrimination they know they will face. They try to do everything they can to avoid going and then when they do, on a scale from 1 – 10, they are already at a 9.” The combined lack of medical education about Sickle Cell Disease, prejudice against people of color, and the national opioid crisis have all made the social implications of the disease very challenging. Dr. Okwerekwu, through public interaction in-person and online through his YouTube channel “Sickle Cell with Dr. O” stressed the importance of raising awareness and educating people about the disease. “The thing with Sickle Cell, even though people may not be directly affected by it or understand what it is, it is a human experience. For me, Sickle Cell represents how everyone has their own personal struggles and if people took more time to listen and empathize with each other the world would be a much better place.” Marco Garcia, C’25, reflected on this community interaction, “One of my favorite memories of the class was getting to meet experts who are working with people suffering from Sickle Cell. Having these conversations opened our eyes to the extent to which Sickle Cell is not just a disease but the social implications of it. We learned how people are turned down for treatment because of racial prejudice. Because of the course, I now realize how important it is for anyone doing research in a STEM field to understand the background of how the research can be for the greater good of society.”

Sustaining Community Partnerships Through Education and Advocacy

The outcome of the “What’s Happening with Philly’s Trees?” project was the incorporation of technology to teach youth about nature. Anisa explained how they used an app as an educational tool. “We knew that the students loved technology. Getting students interested in STEM is one step towards getting them to understand the significance of having trees in the neighborhood. We used the app to increase their interest in ecology and develop an understanding of how trees work. We explained to them as we were using the app how the process of photosynthesis happens, how we need trees to provide oxygen and take in excess carbon dioxide from the environment, and finally, different STEM occupations that they could pursue. We talked about how they could become tree surgeons or horticulturalists, etc.”

For the Sickle Cell project, Kouassi said, the group initially had a difficult time identifying a focus to the project, they had so many ideas. In the end, the students formed a student association, allowing them to do the advocacy, information gathering, and training for medical professionals simultaneously. As Mecky said, “The Penn Sickle Cell Association will allow the students to materialize the components of their project they felt were important, continue to build awareness, and further the conversation.” Similarly, the project on neurobiology and COVID-19 focused on mental health issues and social isolation affecting marginalized youth in communities hit especially hard by the pandemic. According to the student research, “health disparities are affected by socioeconomic health determinants and long-standing structural inequities. In the U.S., African Americans and Latinos have accounted for 21.8% and 33.8% of COVID-19 cases, respectively, yet only make up 13% and 18% of the population.” Out of a partnership with a local middle-school, the Penn students become mentors for the youth they interacted with throughout the project. The long-term potential for this is unknown.

All three projects have components that will continue beyond the course primarily due to, Jean-Marie Kouassi suggested, the strong relationships that were built with community partners. “It was amazing to see how the students discovered that they couldn’t run with their own ideas but had to listen to each other and listen to the community. Through this course, we are building the next generation of holistic scientists, researchers who work beyond the four walls of their lab to consider the contexts in which they work and the communities their work impacts,” Jean-Marie Kouassi said. Ms. Brandon stressed the importance of this community-component of the class, “The community impact piece is critical because you cannot operate in a silo. If you are studying something, you need to know how that will impact those in the community, you need to step outside of the classroom and connect with the community that is impacted.” With funding from the SNF Paideia program, development of this innovative course was possible. “It is a new model for how to teach biology students to think in holistic, community centric ways” Mecky reflected.