Pre-paideia, unbeknownst to me, I held a limited perspective of dialogue. I saw dialogue as merely conversation: a verbal exchange of ideas, thoughts, sentiments between one or more body-minds. I valued difference—my earliest friendships, since kindergarten, were formed across lines of ethnicity, religion, native language. So much of who I am, what I appreciate, and what I delight in is a direct reflection of that early exposure to different cultural practices and ways of being and relating. Later, deepened by the many DBEI trainings and challenging conversations I engaged in as an undergraduate student worker in residential life and, later, as an AmeriCorps member serving with City Year Philadelphia (CYP). Still, my understanding of dialogue and its value was narrow, and I only became aware of this through Paideia—again, because of exposure.

Many people, I’ve learned, share this simple, surface-level view of dialogue: an image of two or more people speaking, exchanging ideas. Yet dialogue is not fixed, nor is it confined to verbal exchange. Its reach extends far beyond what is spoken aloud. To what depths the expansiveness of dialogue stretches—of that I am still uncertain, but I do know I want to explore those depths here.

At first glance, it appears that we exist solely in the material world—within the realm of structure and form. A world of bodies made of bone and fat, of land packed with mineral, of animated species in all their arrangements: trees rooted into the earth, shifting only when the silent winds decide to roar or when the seasons announce their presence through the release of the familiar greens; winged creatures stretching into unreachable heights, levitating within the depths of that steady sapphire vault overhead. And we—these bone bodies—move among other solid compositions of our own making: architectures of brick and concrete, plasterboard chambers, stacked stone structures filled with more stone-solid configurations.

At first glance—but solids are always more porous than they appear. As is the structure of dialogue.

If the solidity of the material world is more fluid than it seems, then so too is the essence of our meaning-making. Behind this seemingly material world there is the inner, silent voice—this mind-place within the body-mind—ever witnessing, processing, distilling, connecting, reimagining. A voice that, in a moment’s notice, can return me to the bare white hallways of Uncle Carlton’s apartment, where it is the birthday of an eight-year-old Keimahney, sashaying down the corridor as her father snaps a quick photo of her before they knock on the door and are greeted by family. A moment where that eight-year-old received her first bike, colorful pink and purple tassels spilling from the handlebars. A voice soft yet loud, ever-present, powerful enough to evade time and space, yet never interacting with the airwaves, never touching the ears. What boundaries this mind-place holds—if any—remain unknown. It is toward that unknowing that we now turn.

How do the invisible, the formless, and the patterned physical world converge? And what does this convergence reveal about dialogue as both an internal process and a visible practice?

In the introduction to Sex Lives: Intimate Infrastructures in Early Modernity (2023), Joseph Gamble articulates the value of the phenomenology of infrastructure, arguing that to understand what lies beneath and holds up a thing (a city, a government, a sex life, or a conversation) is to grasp the concrete operations of what otherwise appears as abstract, theoretical power structures. This understanding makes possible the identification—the naming and calling out—of the real, existing structures at play within any moment, interaction, or conversation.

Gamble, drawing on Lauren Berlant, further frames structure as “the convergence of force and value.” In this sense, infrastructure is not merely material but force-plus-value as lived and felt—experienced subjectively, yet no less real. What may appear immaterial or invisible is, in fact, structured and structuring as it moves through the body and through dialogic encounters, which consist of both the know-how and the feel-how domains. These domains are significant because they are critical contributions to the formation of the whole; to look only at the structure or only at the infrastructure—only at the know-how or only at the feel-how—is to arrive at an incomplete, inaccurate depiction of what is.

Towards the end of the introduction, Gamble introduces Meso-Level Analysis, “[an] analysis that tr[ies] to tarry in and piece apart the circuits and exchanges that connect up the very small (micro) with the very big (macro), a sort of analytic foreplay that indefinitely suspends the spectacular release of macro-level claims in the hopes of inventing other, more contingent forms of meaning-making.” While Gamble locates this analysis within the context of the sex life, I am interested in the meso-space of the dialogic life.

When we view dialogue as both structure and infrastructure—as both external exchange (the lived structure) and internal architecture (the inner mind-place)—what truths about relation, perception, and selfhood emerge?

Let us begin with some workable, iterative definitions, drawing from Gamble’s work. Dialogue as structure refers to the visible, patterned forms of exchange—the frameworks through which communication, relation, and meaning take shape: the breaking of bread, the sharing or utilization of space, the text message sent and received, the journal entry written in a personal notebook, the silent, swift nod of recognition of another passerby on the street. It is the relational patterning of giving and receiving, speaking and listening, the visible currents through which subjectivity and care become perceptible—known and felt.

As infrastructure, dialogue lives beneath the surface as the invisible support: the quiet inner voice; the processing, distillation, and imaginings that take place within the mind-space; the rehearsals that help us navigate the external landscapes of life and society. These inner movements give rise to the lived, embodied patterns that emerge in the world—our relationships, our communities, our systems of meaning.

On this zoomed-in level of relating and dialoguing, the operative forces and values become easier to discern. Forces often materialize as internalized expectations, cultural norms, inherited patterns or social scripts—pressures that move through us, sometimes without our awareness: heteronormativity, for instance, or the many forces bound up in what bell hooks names the imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchy. Values, by contrast, emerge as the priorities we affirm or resist, first in the rehearsals of the mind-space and then in the embodied, external world. Together, these dynamics ripple across the know-how and feel-how domains, producing a particular felt positioning in relation to life and society—our subjective orientation to the world.

Why tend to this terrain of infrastructure, structure, forces, and values? What opens up when dialogue is held as both structure and infrastructure?

To make clear the importance of this perspective, I want to revisit one of the CYP trainings I mentioned earlier—The Water We Swim In—a session that has shaped my thinking ever since.

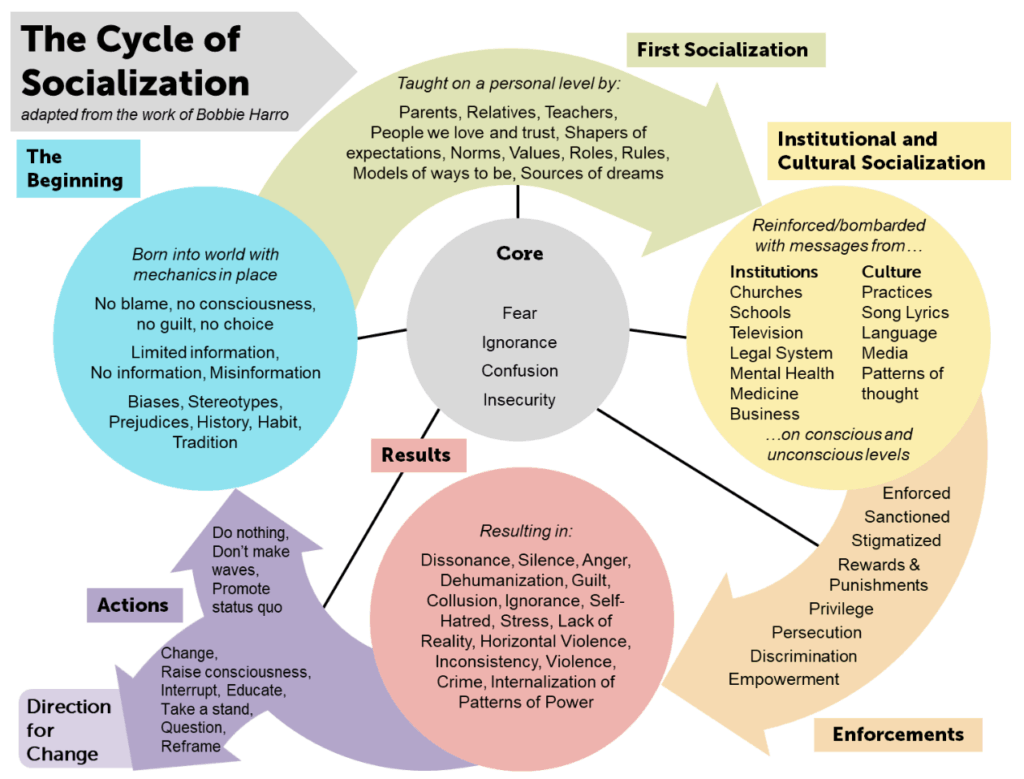

As an overview, the training was a DBIE training that felt multi-purpose—functioning both as an expansion of awareness of the systems, structures, forces, and values active within our society and as an invitation for personal reflection on how these systems and forces have shaped and continue to shape our lives. The Water We Swim In referred to a story used to introduce what is known as the Four I’s of Oppression and the Cycle of Socialization. The story, which may be familiar, goes like this:

Two young fish are swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way. The older fish greets them and says, “Morning! How’s the water?” The two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and asks, “What the heck is water?”

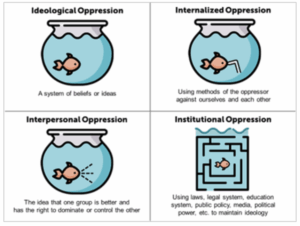

After this story, we were introduced to the Four I’s of Oppression—ideological, institutional, interpersonal, and internalized—to illuminate the process of socialization: how we learn what is “acceptable”, who is valued in the society we’re born into, and how to be in relation to others on this hierarchy valuation. The Cycle of Socialization, drawn from Bobbie Harro’s work, maps this process. It starts with The Beginning, the phase I return to most. In this phase, socialization precedes our birth—our arrival on this planet. Identities such as race, gender, class, and religion are assigned to us before we take a breath, without our choosing, and we enter a world whose laws, rules, narratives and hierarchies are already fully formed. We have no hand in constructing them, yet we are born into them all the same—into systems shaped by histories, traditions, and myths long established. Because we arrive without consciousness of self or structure, we absorb these preexisting norms, expectations and scripts as simply what is—The Water We Swim In. In this way, socialization is both inherited and invisible, establishing the foundation of the forces and values that rather expediently shape our subjective positioning in dialogue—what we perceive, internalize, resist, and believe is possible.

For a fuller exploration of the Cycle of Socialization, you can find the City Year Philadelphia resource PDF linked here.

Thus, what is at stake in viewing dialogue as both structure and infrastructure is the emergence of clarity, self-actualization, and what the Anishnaabe articulate as mino-binaadiziwin—the good life. Dialogue enables exposure and illumination precisely because it is patterned as we are—structured yet malleable, seemingly fixed yet endlessly capable of transformation. This matters because awareness of the looseness of this infrastructure—this patterned mattering—blurs the boundaries once assumed as fixed, expanding the range of what becomes possible. It allows me—and anyone—to exercise autonomy, to make intentional choices about the life one seeks to build, and to engage in dialogue across difference, power, and experience with intention rather than inheritance.

With this awareness, I can begin to mitigate the impact of the forces at play within my (dialogic) life or exchange outdated, inherited values for ones more aligned with who I am interested in becoming. Internal dialogue becomes a site of (re)patterning—a way of rehearsing for living on terms other than the status quo I was born into. In this sense, dialogue as infrastructure is dialogue as rehearsal.

How do I identify the alternatives that offer real livability? How do I know what is in alignment with who I am becoming?

Here, I draw from Chapter 13—On Black and Indigenous Relationality: A Conversation—published in Gina Starblanket’s book Making Space for Indigenous Feminism (2024). The chapter is a recorded discussion among Robyn Maynard, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Starblanket. In this conversation, Maynard posits that “if we think about movements as dress rehearsals for trying to create the lives that we believe we deserve…those kinds of transformations end up having an afterlife well beyond a particular movement’s success or failure. We inherit a multitude of ‘timelines of otherwise’”.

Maynard further emphasizes the significance of the term rehearsals in its plural form, underscoring the infinite and unfinished nature of the process. Rehearsal becomes an entry point into understanding movements—and, by extension, dialogue—as “heterogenous locations through which freedom work” persists beyond the temporal and spatial boundaries we tend to assign to them.

In the dialogic context, these afterlives and alternative timelines often surface as subtle ripples: a lingering thought, a replayed phrase we offer to someone else, the cultivation of a new dialogic space, a comment we return to again and again—working on us long after the conversation has ended.

Dialogue is freedom work: a way of making something otherwise, of testing alternative realities, of reimagining what might be possible.

Rehearsal then becomes a way of experimenting with which combinations of forces, values, and subjectivities can truly hold me. Because the interplay between the internal and external is constant, rehearsals never remain solely within the mind-space; they take form through exchange. To sit with dialogue as both structure and infrastructure is to recognize that transformation begins in the meso-space—the hinge between the two—where livability is worked out moment by moment in the body.

Rehearsal helps me to discern what is both good and sustainable. In rehearsal, I engage in the dialogic work of clarifying, reclaiming, and reimagining. In rehearsal, I can ask:

- Does this role allow me to breathe?

- Does this response align with my values?

- Can this identity story carry me without collapse?

It is here that dialogue becomes not only a way of relating, but a way of living otherwise.

Keimahney Carlisle is Fellows Program Coordinator, SNF Paideia Program.

This entry is part of DiaLogic: Thinking Through Big Questions for Dialogue, a monthly series in which SNF Paideia Dialogue Director Dr. Sarah Ropp and guest contributors from the SNF Paideia community explore key questions and share ideas, experiences, resources, and practices related to diverse dialogue topics. We invite you to respond with your own thoughts and ideas in the comments. If you’re interested in contributing an essay or if this post sparks any ideas about collaborating to create more dialogue at Penn and beyond, please reach out directly to Sarah Ropp at sropp@upenn.edu. For more DiaLogic posts, visit this page here.