What Good Shall I Do This Day?

Benjamin Franklin left us with the well-known idiom “What Good Shall I Do This Day?”. Although there are contexts in which the good is quite clear, we also live in a complex world in which “the good” is often not obvious. After all, had it been clear, we should not be facing so many seemingly insurmountable divisions of ideas and thoughts.

I do not have an answer to the age-old question of what “good” is, however, I do understand one way to get beyond disagreement is through intentional dialogue which requires close attention to the words we use. Especially in an age where information spreads very rapidly, often in the form of provocative short sentences or slogans, closer attention to the meaning behind the words we use can be of benefit to our conversations.

Do We Really Mean “Rational” in Economics?

My thesis [1], which also turned into a SNF Paideia Capstone project, is an example of such a reflection. I investigated the use of the term “rationality” in economics, and whether the espoused economic definition really captures the “rationality” or not. As a student who studied economics and philosophy simultaneously, I gained a unique perspective of how the word “rationality” is used to mean different things in the two fields. The assumed definitions in economics did not quite fit into the discussions in philosophy, and vice versa. This incongruity piqued my curiosity.

After doing literature research on the term, “rationality”, I ended up arguing that “rationality” as used in economics does not quite capture what we mean when we say “rational”. The word “rationality” in economics often shows up in models of consumers, where they are assumed to be “rational” as far as their preferences fulfill certain requirements. For example, they have a requirement that the preference needs to be transitive. If you prefer chocolates to cookies and cookies to cakes, you must prefer chocolates to cakes or otherwise you are irrational.

The requirements do not seem absurd at first sight. They do seem to capture what rationality is. However, upon a close investigation, it turns out that such is not true. For example, they cannot call Buddhist monks rational if they exhibit minimalist behaviors, preferring nothing more than what they need. They have preferences for goods just to the extent they need them, and there is nothing irrational in such preferences. However, the “rationality” in economics misses these people because they violate what they call monotonicity – more of what is preferred is always preferred than less of it.

What Can Happen When We Reflect on Words

Overall, it seems to be that “rationality” as used in economics is a crystallized definition reflecting a long historical development of thought. I do not think such changes in definitions are bad things in themselves. Nor am I arguing against the economic models that use “rationality” assumptions. The economic models can be great ways to understand the world, as long as they describe or predict the world as needed. However, the accuracy or precision of models is an empirical question separate from the conceptual point I am making.

Given that economic “rationality” does not quite capture the essence of the word “rationality” as we use it, we can look for alternatives. One of the alternatives that I suggest in my thesis is a philosophical one, as broadly understood. The philosophical definition says, what it is to be rational is to take (or not take) an action supported as the best, considering all relevant reasons. One may think this debate only serves those who are pathologically obsessed with words, but I do not think that is true.

“Rationality” is ubiquitous in the United States, especially in policy conversations, although it is often implicit. For example, we tend to think that as long as people are acting rationally, we should support their free choices. If people are acting irrationally, it is easier for other people to justify their interventions, at the cost of the choice. We may think we should intervene in an attempt to get them to be more “rational”, on an assumption that deep down, everyone wants to be more rational.

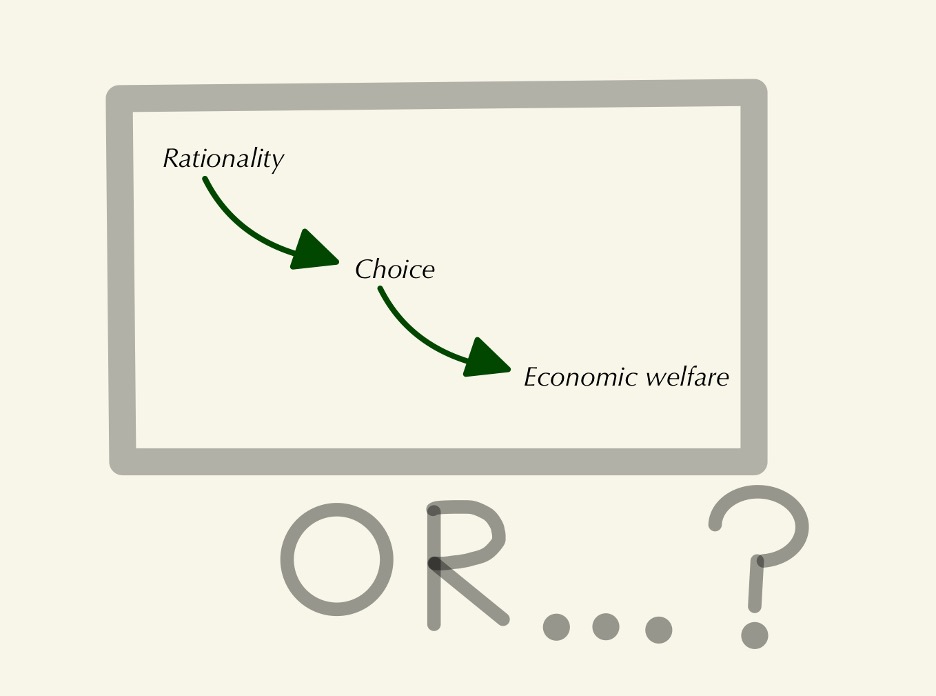

However, when the “rationality” in policy conversations is interpreted as economic “rationality”, the conversation goes even further. Economists, or people who are economically educated, often think as follows. Under the economic account of “rationality”, we see that many people are acting rationally (when they are not, we delegate the task to behavioral economists). As far as people are rational, we do not see any argument for confining their free choices built upon rational choices. Given that the economic “rationality” says that the choices reveal preferences and if the satisfaction of preferences define welfare, the aggregate of these choice satisfactions is what we can take as an economic “welfare”. Then, we should be trying to maximize the economic welfare as a society and policies should reflect that (unless the economic welfare fails to capture “externalities”, an impact of individual choices on other people whose preferences were not included in choices).

The maximization of the economic welfare is often further phrased as efficiency, because more efficient we are in converting resources to preference satisfactions, more aggregate preference satisfaction we should be getting. Each of these statements can be debated, but we can see that rationality plays a crucial role in this kind of reasoning. If we doubt that the economic “rationality” is not really the “rationality” we want to capture, then we have a reason to doubt the whole argument, including the efficient maximization of economic welfare as a supreme good.

One of the policy conversations that reflects this view is the conversation about health policy. For example, in talking about whether the United States should implement government-sponsored universal health coverage, we tend to have a group of people arguing against it based on decreased efficiency for a new treatment or pharmaceutical development. In contrast, we also tend to have people who support UHC regardless of other considerations on the basis of human rights. While both positions can make perfect sense, it tends to be difficult for someone in one position to try to understand another.

However, given the analytical argument of my thesis, it can be easier for someone who firmly believes in the efficiency view to understand another party. If one can see that the view one supports can have vulnerabilities and uncertainties, or even a reasonable way to doubt their argument, this could aid in having more humility in our conversations. The other side, of course, can do the same as well. Although the rights are considered absolute by definition, we also encounter many cases in real life where the pursuit of two rights is not possible, at least simultaneously. We do and we have to, in practice, relax the absoluteness of rights all the time. Knowing this about rights can, I believe, aid the discussion.

Bridging the Disciplinary and Ideological Divisions

What I said above is only an example. It does not even scratch the surface of all the civic conversations happening in our society. However, if there is one thing we could extrapolate from this, I think it is that it could help us to reflect on words we use, instead of assuming their definitions. The ones individually used almost indefinitely come from complex thought traditions, but the history of traditions does not automatically make them right, absolute, or indefeasible.

Instead of adamantly sticking to what we think is right, based on how we have always defined words, we could have a vulnerability to doubt our assumptions and definitions. Checking the way we speak is undoubtedly tedious, but it could take us a step forward toward understanding.

[1] Shrai, A. (2023). “Is the Stable Preference-Based Utility Maximization a Good Account of Economic Rationality?” Joseph Wharton Scholars. Available at https://repository.upenn.edu/joseph_wharton_scholars/148