During our time in Greece, we visited the US Embassy, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and various community organizations. There was ample time for questions at each location, during which our course leaders Professor Fernando Chang-Muy and Professor Fariha Khan encouraged us to delve deeper into the topics we explored in our final research papers. These discussions demonstrated just how powerful in-person, open-ended conversations can be in academic research, as our hosts provided valuable insights into how ethnic identity functions in Greece.

Coming to this realization, after the trip, I couldn’t stop thinking about my term paper. I had chosen to study the demographic makeup of the Black student population at elite higher education institutions in the US, discovering that Black immigrants compose a disproportionate percentage of the student body. While Black immigrants are around 10% of the population of college-aged Americans, they represent 40.7% of the Black student body at elite universities.

While I learned so much about the social context of race in Greece during our time there, their system fundamentally differs from the US in numerous ways. As such, I found it difficult to compare what I had discovered in my final paper to what I observed in Greece.

Given the interdisciplinary nature of the SNF Paideia program, I knew from a previous Africana Studies class that Black immigrants faced the opposite situation “across the pond” — they are actually underrepresented in the British higher education system.

With encouragement from Professors Sarah Ropp and Lia Howard, I applied to the SNF Paideia Small Grants Program, which provided me with funding to travel to London over fall break to continue my research in this area. While abroad, my goal was to gain deeper insights into the structures in place that influence the college application process and representation in higher education. As part of my research, I dedicated significant time to investigating the impacts of immigration policy and the social construction of the Black identity—two areas I chose to focus on in London. Before arrival, I sought out sites of interest for my visit, looking into areas that highlighted the Black experience in the UK.

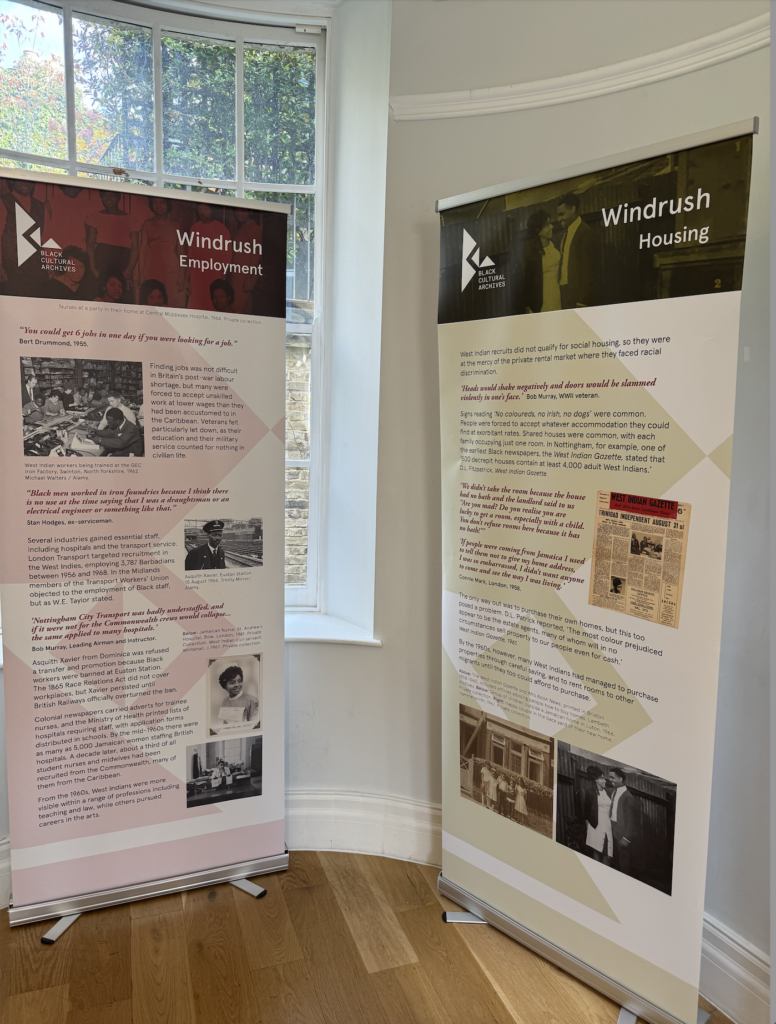

With encouragement from Professors Sarah Ropp and Lia Howard, I applied to the SNF Paideia Small Grants Program, which provided me with funding to travel to London over fall break to continue my research in this area. While abroad, my goal was to gain deeper insights into the structures in place that influence the college application process and representation in higher education. As part of my research, I dedicated significant time to investigating the impacts of immigration policy and the social construction of the Black identity—two areas I chose to focus on in London. Before arrival, I sought out sites of interest for my visit, looking into areas that highlighted the Black experience in the UK.  The first stop on my itinerary was the Black Cultural Archives (BCA) in Brixton. Founded in 1981, it sheds light on the history of African and Caribbean individuals in the UK. It provided me with valuable information on migration, employment, and housing trends for the Windrush generation, or the main influx of Caribbean immigrants to the UK. The museum also included a comprehensive timeline of Black British history from 100AD to the present, detailing major events, legislation and experiences. Initially, I was impressed that the British had constructed such a site. Yet, what I soon discovered cast the BCA in a new light.

The first stop on my itinerary was the Black Cultural Archives (BCA) in Brixton. Founded in 1981, it sheds light on the history of African and Caribbean individuals in the UK. It provided me with valuable information on migration, employment, and housing trends for the Windrush generation, or the main influx of Caribbean immigrants to the UK. The museum also included a comprehensive timeline of Black British history from 100AD to the present, detailing major events, legislation and experiences. Initially, I was impressed that the British had constructed such a site. Yet, what I soon discovered cast the BCA in a new light.

During my trip, I made a pointed commitment to engage in dialogue with London natives (following our professors’ example in Greece). In a conversation with a University College of London student who had grown up in the area, I mentioned that I had traveled to Brixton (not thinking much of the few transfers it took to get there on the tube). Her immediate response was: “Did you feel safe? That’s the ends!” Then, I realized that this vibrant hub of Black culture and history had been quartered “on the other side of the tracks.”

During my trip, I made a pointed commitment to engage in dialogue with London natives (following our professors’ example in Greece). In a conversation with a University College of London student who had grown up in the area, I mentioned that I had traveled to Brixton (not thinking much of the few transfers it took to get there on the tube). Her immediate response was: “Did you feel safe? That’s the ends!” Then, I realized that this vibrant hub of Black culture and history had been quartered “on the other side of the tracks.” Though the museum contained a wealth of valuable information about the Black experience in Britain, housed under the quote: “Black history is British history,” I realizedthat so many individuals would never see this part of Britain for fear of the surrounding area. The student also told me that this area is one of Britain’s most culturally diverse, reminding me of the patterns of social and economic inequality that plague America.

Though the museum contained a wealth of valuable information about the Black experience in Britain, housed under the quote: “Black history is British history,” I realizedthat so many individuals would never see this part of Britain for fear of the surrounding area. The student also told me that this area is one of Britain’s most culturally diverse, reminding me of the patterns of social and economic inequality that plague America.

Next, I visited the Africa Centre, which similarly was a trek from the main public transit routes. Rather than a traditional museum, the Centre is a hub for community engagement. It features a blend of Black entrepreneurship, art, and coalition: the first floor is a restaurant serving traditional African food, the second is dedicated to gallery space, and the third contains meeting rooms. It was lovely to see that there was a space for modern Black Brits to engage with each other.

Next, I visited the Africa Centre, which similarly was a trek from the main public transit routes. Rather than a traditional museum, the Centre is a hub for community engagement. It features a blend of Black entrepreneurship, art, and coalition: the first floor is a restaurant serving traditional African food, the second is dedicated to gallery space, and the third contains meeting rooms. It was lovely to see that there was a space for modern Black Brits to engage with each other.

Finally, I visited The Museum of London Docklands, which highlighted first-hand accounts from Black immigrants in the UK. Reading their stories added nuance to my understanding of the cultural context of immigration and the social construction of the immigrant identity in Britain. However, I was disappointed that much of the museum was geared towards a younger audience. The main exhibit pertaining to Black history— “London, Sugar, and Slavery” —was tucked away in the corner of the top floor. I had hoped to see a more sophisticated discussion and presentation of the issues that have shaped the Black community today.

Finally, I visited The Museum of London Docklands, which highlighted first-hand accounts from Black immigrants in the UK. Reading their stories added nuance to my understanding of the cultural context of immigration and the social construction of the immigrant identity in Britain. However, I was disappointed that much of the museum was geared towards a younger audience. The main exhibit pertaining to Black history— “London, Sugar, and Slavery” —was tucked away in the corner of the top floor. I had hoped to see a more sophisticated discussion and presentation of the issues that have shaped the Black community today.  Over the weekend, I was able to visit some of London’s breathtaking monuments and explore its beautiful historic neighborhoods. I learned about global history at the British Museum, stopped by the Houses of Parliament, sat for high tea in South Kensington—and of course, posed in front of an iconic red telephone booth. In classic tourist fashion, I also spent an afternoon in the heart of Westminster to see Big Ben, the London Eye, and Buckingham Palace.

Over the weekend, I was able to visit some of London’s breathtaking monuments and explore its beautiful historic neighborhoods. I learned about global history at the British Museum, stopped by the Houses of Parliament, sat for high tea in South Kensington—and of course, posed in front of an iconic red telephone booth. In classic tourist fashion, I also spent an afternoon in the heart of Westminster to see Big Ben, the London Eye, and Buckingham Palace.

Instead of becoming disheartened with Britain’s lack of a racial reckoning, my trip to London inspired me to continue looking into how immigration policy and social perception can influence enrollment at top universities in the US and the UK. I’m so grateful to SNF Paideia’s generous funding for this opportunity, which allowed me to conduct meaningful research while making unforgettable memories abroad—a chief goal of mine in attending a global university such as Penn.

Olivia Reynolds (C’26) is a junior in the College of Arts and Sciences, studying political science on the pre-law track, and serves on the SNF Paideia Advisory Board.