Overview of Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence

For the second post in our Decolonizing Dialogue series (see here for an introduction to the series + the first post on Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire), I’m reading Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence: Understanding and Facilitating Difficult Dialogues on Race (2015) by Derald Wing Sue. Derald Wing Sue is the son of Chinese immigrants and currently Professor of Psychology and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. His scholarly interests include multicultural counseling, the psychology of racism and antiracism, cultural competence, and mental health law, among others.

For the second post in our Decolonizing Dialogue series (see here for an introduction to the series + the first post on Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire), I’m reading Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence: Understanding and Facilitating Difficult Dialogues on Race (2015) by Derald Wing Sue. Derald Wing Sue is the son of Chinese immigrants and currently Professor of Psychology and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. His scholarly interests include multicultural counseling, the psychology of racism and antiracism, cultural competence, and mental health law, among others.

Race Talk is a follow-up to the impactful book Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation (2010), co-authored by Sue and Lisa Spanierman. In Race Talk, Sue proposes that there is a “conspiracy of silence” around race in U.S. culture. He analyzes the cultural and psychological reasons that people in the U.S. find talking about race and racial (in)justice so anxiety-inducing — an anxiety that he demonstrates exists among people of all racial backgrounds, though for different reasons and sometimes in different manifestations. Sue also offers guidelines and strategies for participating in dialogues about race at home, at work, and in the classroom. Throughout each chapter, Sue refers to both anecdotal personal experience (his own and others’) and academic studies from a variety of disciplines, including psychology, sociology, education, and business, to provide evidence for his claims. He demonstrates not only the deeply embodied difficulties of race talk, but also its documented benefits.

Sue emphasizes, “Racial dialogues are one means by which we can impact the racial realities of Whites by making them racially/culturally aware, raise critical consciousness of the systemic forces of racism, and motivate them to consider changes at the individual, institutional, and societal levels” (188). He provides abundant and convincing evidence for this throughout the book. What I found missing, though, was a similarly detailed discussion of the benefits of racial dialogues for people of color, whether in-group dialogues with members of one’s own racial or ethnic group, intergroup dialogues with people of color from other ethnoracial groups, or intergroup dialogues that include White people. Besides the eventual trickle-down effect of White critical consciousness leading to anti-racist action leading to social change, what might folks of color be getting more directly out of these conversations when they are successful? Perhaps Sue feels the answer is self-evident and therefore doesn’t need to be “proven” (we can guess at some possibilities: solidarity, validation, a sense of feeling seen and heard, a greater sense of belonging, healing…?). One other important note is that while Sue emphasizes the importance of racial dialogue for all ethnoracial groups, the examples he references draw mainly on African American and Asian American experiences, issues, and stereotypes.

Although Sue doesn’t use the word “decolonial” to frame his analysis, he explicitly describes the major barriers to authentic, meaningful racial dialogue as the result of White, Western social constructs and systems of domination that continue to be imposed on Indigenous, Black, Latinx, and Asian people in the U.S. Successful race talk, in Sue’s formulation, depends on acknowledging the damage these imposed constructs and systems have done to all of us — including White people — and learning to honor non-White and non-Western ways of speaking, listening, knowing, and being.

Major Concepts & Opportunities for Reflection: Conspiracy of Silence, Master Narrative vs. Back Talk, Communication Styles, and Guidelines for Dialogues on Race

Here are some of the anchoring concepts from Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence. For each one, I’ve suggested a few questions, inviting you to dialogue with Sue’s ideas through the lens of your own values, experiences, and goals.

Conspiracy of Silence: Sue contends that there is an unspoken pact in U.S. culture that issues related to race — identity, experience, and systemic oppression — are “off-limits” for discussion, especially in the public spheres of education and the workplace. He calls this unspoken pact, and the myriad unofficial “ground rules” that serve to support it, a conspiracy of silence. In Sue’s analysis, this conspiracy of silence primarily serves to protect White people from having to reckon with the present-day reality of ongoing racial injustice, its long history, and the various ways they have inevitably benefited from and participated in the oppression of people of color. That is, “race talk is frightening because it threatens to destroy the fabric of naïvete and innocence” that blankets White consciousness (91). If White people start talking honestly about race, they/we might have to acknowledge racial injustice; once they/we acknowledge racial injustice, they/we have to confront their/our own responsibility in combating it.

The conspiracy of silence is built upon three main protocols that Sue identifies as fundamental to middle class White/Western culture: the politeness protocol, the academic protocol, and the color-blind protocol. Socially and politically, both White people and people of color are rewarded for remaining dispassionate, conciliatory, and “objective” when discussing race. Meanwhile, people of color suffer consequences for speaking honestly in public about their experiences of humiliation, disempowerment, and dehumanization as non-White people. Thus, White/Western protocols are enforced upon all of us, and the performance of these protocols is necessary to be successful in White-controlled institutions. The graphic below outlines the three protocols that impede authentic race talk in more detail (available to download as a PDF here). As you read through it, think about the following questions:

- Think about conversations you’ve participated in related to race, or conversations about other things in which race came up. Did you see evidence of any or all of these protocols playing out in other people? What did that look like, and what was the effect? In retrospect, did you unconsciously perform any of them?

- How are you and the work you do (whether scholarly work or civic engagement) affected by each of these protocols? In what ways do you feel each one has harmed and/or protected you in thinking or talking about race?

- Which one of these protocols do you feel you, personally, most urgently need to resist, and why? What would resistance look like for you in terms of concrete, realistic actions? What would be difficult about resisting these protocols for you, and how might you cope with that?

Master Narrative and Back Talk: “Race talk often reenacts the entire history of race relations in the U.S.,” particularly in the way participants tend to embody longstanding, competing narratives, Sue notes (37). The master narrative (what Sue and other scholars also call “White talk”) is the official, dominant, colonial narrative of U.S. history and present-day. According to the master narrative, the U.S. is a successfully democratic, morally good society of equal access and opportunity, in which truth and justice are valued and prejudice, discrimination, and racism are individual pathologies, not structural realities (38). The United States is understood as a White, Christian nation which absorbs other groups into itself via a “melting pot” that requires acceptance of the master narrative as the price of admission. Therefore, just as with the protocols outlined above, many people of color have internalized the master narrative to some degree as a matter of survival. Back talk, on the other hand, is a counter-narrative or “hidden transcript” that contradicts the master narrative and “unearths ugly secrets of how Whites’ advantaged positions are attained through oppression, power, and privilege” (37). Because it is deeply threatening to White people’s perception of themselves as good, decent, moral individuals, back talk is dismissed and delegitimized on the basis of the protocols outlined above. That is, back talk by its nature is considered “impolite” and is, in addition, often expressed with a degree of emotion or reference to personal experience considered “unscientific” and “irrational” by White/Western rules.

- Where have you seen the “master narrative” being reinforced in your family, community, school, or workplace? Do any of the individuals or institutions in your life that support the master narrative surprise you?

- Were you brought up to adhere to some version of the master narrative? Were you exposed to any back talk as you were growing up, and if so, was it by accident or on purpose? Were you encouraged to believe or dismiss back talk?

- What is the relevance of the concepts of “master narrative” and “back talk” to your personal role in scholarship and/or civic engagement? That is, how might the ways in which you’ve been trained to pursue knowledge and research or try to effect change in your communities have been colonized by the master narrative? How might they be transformed by the “back talk” narrative?

Communication Styles: Sue stresses that it is not just the imposition of White/Western protocols and narratives that silence race talk, but also the imposition of White/Western communication styles. Because Whiteness is generally not recognized as a distinct racial or cultural category, White styles of verbal and nonverbal communication are treated as a “neutral” or universal standard from which alternative styles deviate, rather than simply one of many culturally specific styles. Sue discusses examples from Asian American and African American communication styles in contrast with dominant White communication styles to demonstrate how, although typical Black and Asian styles of communicating are very different from each other, both are disrespected and disregarded in White-controlled spaces. Again, people of color must adapt to the “White way” to be listened to, even to be seen; that means striking what is considered the “right” balance between restraint and passion, deflection and directness, deference and assertiveness. Sue notes that “differences in communication styles are most strongly manifested in nonverbal behaviors that transcend the written or spoken word” such as proxemics (use of (inter)personal space — think proximity and distance), kinesics (bodily movements like facial expressions, gestures, eye contact, posture, nodding, etc), and paralanguage (vocal cues like loudness, pace, inflections, pauses, etc) (118). For race talk to be authentic, participants from all ethno-racial backgrounds need to become more aware of differences in communication styles and realize that many common “ground rules” for dialogue are not neutral or universal but rather implicitly reinforce White standards for what “civil conversation” should look like.

- How would you describe your own communication style in terms of proxemics, kinesics, and paralanguage? Is it generally similar to how others in your family or community communicate? If not, what do you think might account for the difference?

- Thinking about classroom or community conversations you regularly participate in, what are the (spoken or unspoken) norms for how people are supposed to interact with each other? Do those norms make space for “non-standard” communication styles? If so, how? Thinking about who is present during those conversations, who tends to participate the most? What do you think the relationship is between the norms that have been established and the people who seem most comfortable speaking up?

- What communication styles do you find most difficult or uncomfortable to engage with? (Again, think in terms of proxemics, kinesics, and paralanguage, if that’s helpful.) Where do you think that difficulty or discomfort comes from? How do you usually cope with it (i.e. by opting out of the conversation altogether; matching your communication style to theirs; asking them to alter their communication style; etc)? Is this a successful strategy, usually?

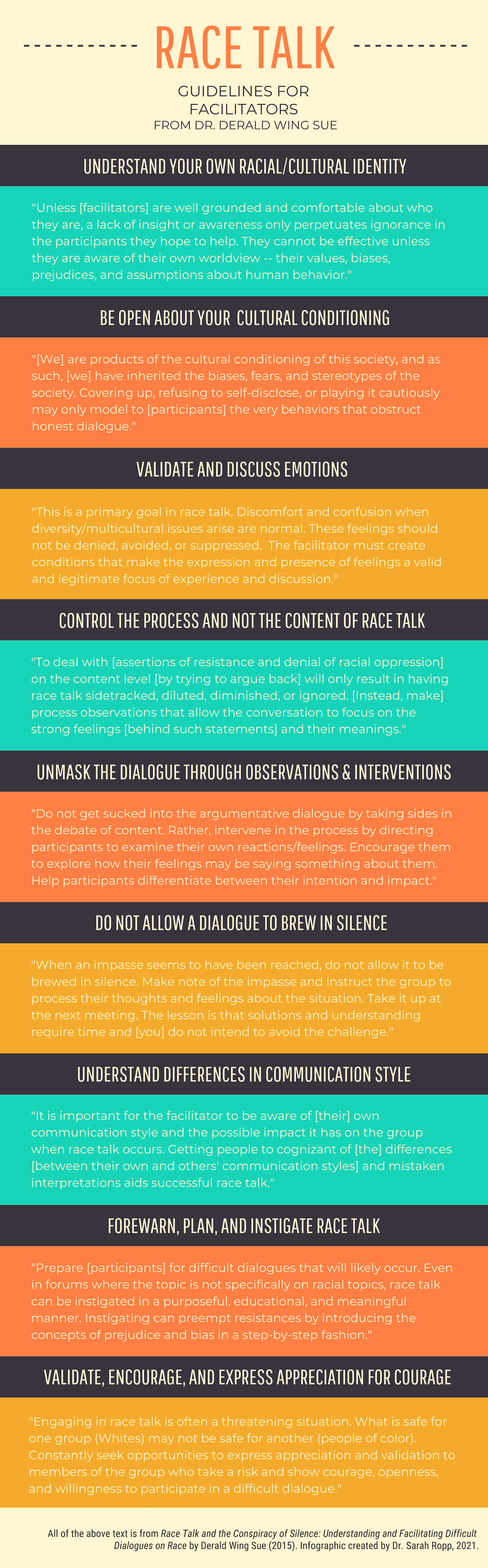

Guidelines for Facilitators: Finally, Sue presents some strategies at the end of the book to help facilitators of dialogues on race (or dialogues in which race “comes up”), summarized in the graphic below (available to download as a PDF here). As you read through them, reflect on prior conversations you have had about race and how tensions were handled.

- Which of these guidelines might have made a difference? Are there additional guidelines you feel might be missing?

If you like this content and want more, follow us on social media and subscribe to our listserv.