Overview of Integrating Mindfulness into Anti-Oppression Pedagogy

This week, I’m reading Integrating Mindfulness into Anti-Oppression Pedagogy: Social Justice in Higher Education by Beth Berila (2016).

(For an intro to the Decolonizing Dialogue series + the first post on Paulo Freire, see here; for last week’s post on Race Talk by Derald Wing Sue, see here.)

Beth Berila is Director of the Gender and Women’s Studies Program and Full Professor in the Ethnic, Gender, and Women’s Studies Department at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. According to her website, “she integrates mindfulness and somatics into her work in unlearning and healing from oppression in order to co-create individual and collective liberation.” Integrating Mindfulness is Berila’s first book, informed by fifteen years of teaching feminist and women’s studies courses as well as her longtime yoga and meditation practices.

In the book, Berila notes that college courses on topics related to social justice and diversity — such as Ethnic Studies, Women’s and Gender Studies, LGBT/Queer Studies, Multicultural Education, Sociology, and so on — generally succeed in helping students understand injustice and difference on an intellectual level. They often evoke strong emotional reactions as well, as students connect to anger, grief, shame, and/or a desire to take action against inequality. However, Berila argues, social justice teaching and learning usually stops short at reaching the deepest level of knowing — the body. If we want to heal from and unlearn oppression, we must become aware of the ways in which oppressive ideologies and experiences have encoded themselves in our bodies. Berila proposes that mindfulness, as a set of practices through which we can develop this crucial self-awareness, is a necessary addition to social justice work. That includes the difficult and messy conversations that form so much of that work.

Berila locates mindfulness practices within a feminist pedagogy that seeks to educate the whole person, co-create knowledge together with students, and attend to the body as a source of knowledge: a site of oppression, pain, and violence but also a site of resilience, pleasure, and care. That means attending to the body conceptually in the content of the course (i.e., reading, writing, and talking about the lived impact of the ways in which human bodies are socially defined in terms of gender, race, and ability). It also means acknowledging and drawing on knowledge from the actual, living bodies of the students and teachers within the classroom space. Though Berila argues that these ideas are also relevant to critical, anti-racist, and queer pedagogies, the examples she draws from in the book mainly focus on her experiences teaching intersectional Women’s Studies courses. In her final chapter, Berila effectively addresses critiques, such as concerns around cultural appropriation represented by drawing on Eastern practices, the implications of secularizing practices that are originally spiritual, and misunderstandings of mindfulness as feel-good escapism.

Ultimately, the focus on mindful embodiment that Berila advocates is a decolonial approach because of the way in which it challenges Cartesian duality — the binary separation of mind from body that has defined the Western sense of self as well as the Western approach to education (41). Thus, even when the course or the conversation is not “about” challenging coloniality, to treat bodies (including students’ bodies) as sources of meaningful knowledge is to work towards the decolonization of our educational spaces and the dialogues we pursue inside and outside of those spaces.

Major Concepts: Anti-oppression Pedagogy, Mindful Embodiment, the Witness, and Contemplative Practice

Here are some of the anchoring concepts from Integrating Mindfulness. For each one, I’ve suggested a few questions, inviting you to dialogue with Berila’s ideas through the lens of your own values, experiences, and goals.

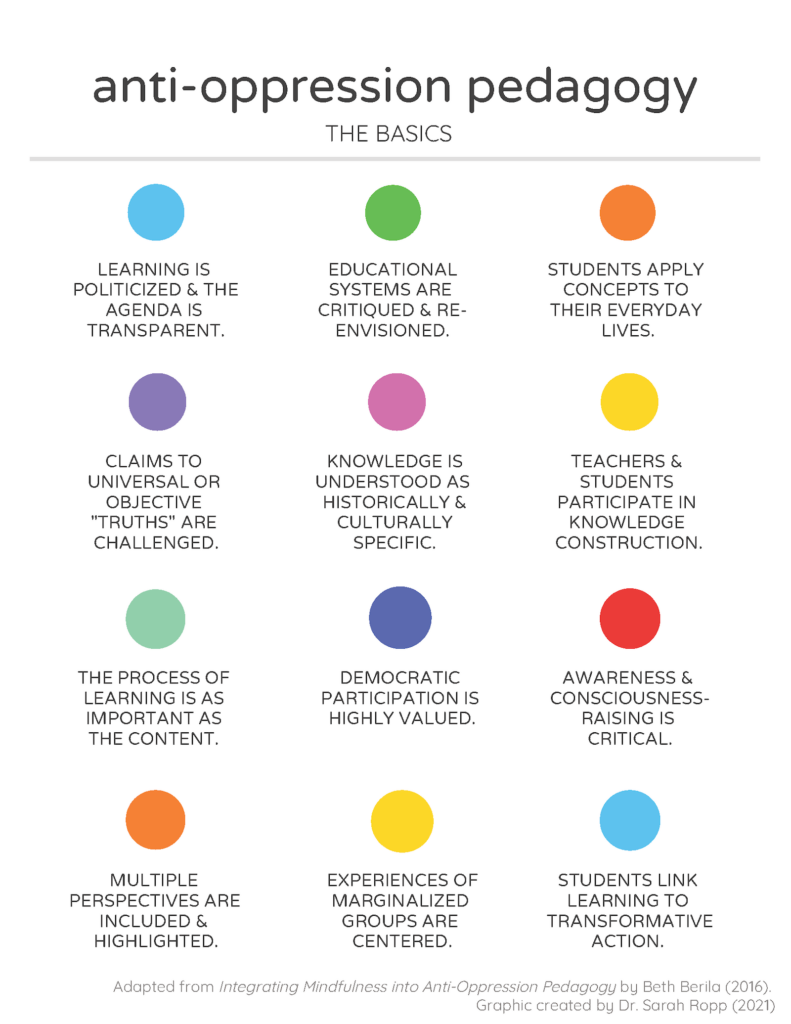

Anti-oppression pedagogy: Berila summarizes the basic features of anti-oppression pedagogy, which she uses as an umbrella term to unite four approaches to teaching and learning that have grown from particular sociopolitical and academic movements: critical pedagogy, feminist pedagogy, anti-racist pedagogy, and queer pedagogy. Though she emphasizes that there are some significant differences between these pedagogies, Berila notes about a dozen core commonalities, presented in the graphic below. (Download a PDF of the graphic HERE, or access a plain-text version HERE.) As you read through these 12 main features, consider the following questions:

- Have you ever experienced a learning environment of any kind (at school, at home, or in your community) in which any of these practices and principles were applied? If so, which practices and principles were successfully achieved, and what was the effect for you? Which ones were attempted, but unsuccessfully? Why do you think they failed? If not, why do you think you have not yet encountered such a learning environment? What do you think the effect has been on you and your learning?

- Which of these 12 principles most appeal to your values? Which do you think your learning style would most benefit from? What are concrete actions that you might take to apply those principles in the environments in which you are a learner and/or a leader?

Mindful embodiment: “Embodiment,” writes Berila, “refers to the imprints and manifestations of power, ideology, and socialization on our very bodies. . . . Embodiment is interested in how we know what we know at the level of the heart and the body, rather than the merely static, cognitive, mostly cerebral focus of more traditional, Eurocentric, and androcentric knowledge” (36). Mindful embodiment, then, is about tuning in to the ways our bodies are processing and responding to complicated and challenging ideas (such as ideologies radically different from our own); feelings (such as the grief, rage, shame, disgust, or hopelessness that we might experience when we realize our own oppression, encounter others’ difference, or confront our privilege); and experiences (such as microaggressions, challenges to our ideas, or witnessing others’ pain). The pursuit of mindful embodiment is an attempt to make those deep, often unacknowledged processes of response “visible, consciously experienced, and open to critical inquiry” (37).

Mindful embodiment, Berila explains, is also about discovering and working to repair the imprints that oppression have left on our bodies (as well as our psyches, our hearts, and our minds). Those imprints include internalized oppression, or the negative messaging about oneself or one’s community that one has unconsciously accepted as truth, even if they understand on an intellectual level that they shouldn’t feel this way. Internalized oppression is the sense of instantaneous disgust in a woman or femme’s gut that tells her she looks “gross” for having gained weight, or that urges a working class person to deride members of their same social class as “trash.” Other deeply embodied imprints of oppression include those conditioned responses on the basis of stereotypes and biases that we may deny consciously but that we experience in our bodies nevertheless. These responses register as the jolt of alarm when a man of color approaches, the inability to make eye contact with a person in a wheelchair, the unconscious urge to speak louder to someone who looks or sounds “foreign,” and so on. Since almost all of us are oppressed in some ways and privileged in others, we each carry complex constellations of imprints.

- What is your response to the concept of “mindful embodiment”? Is there anything here that you can relate to or recognize?

- Can you think of moments during encounters with different people or ideas — in class, in your community work, on the street — when your body reacted strongly? (Think about a pounding heart, sweating, trembling hands, a shaky voice, the sense that your eyes were skittering around, the sudden urge to fidget, etc.) Looking back, where do you think those reactions came from? How did you respond to your body in that moment?

Witness: The critical tool for becoming aware of how moments of difficulty and tension are registering in our bodies and directing our reactions is what Berila calls “the Witness.” The Witness is “the ability to observe what is happening. Rather than drowning in our experiences, the Witness lets us be bigger than our emotions. It is the ability to be present with what is happening without being consumed by it” (79-80). Thus the Witness is a cultivated ability to notice, name, and accept the physical and emotional response you are having in any given moment with a sense of “nonjudgmental compassion” (81). To pause, slow down, notice, and name your own reaction without moving immediately to ignore it, deny it, reject it, transmute it, or shame it is, Berila argues, a crucial step in learning how to intervene in and change our harmful responses (whether self-harming, as in the case of internalized oppression, or other-harming). That is, although it might seem paradoxical, by not immediately judging ourselves for our reactions but instead sitting with them and accepting that this is the reaction we are having, we can begin to understand that oppression is learned, not innate to our very being (112). That understanding empowers us to begin to unlearn it.

The graphic below presents Berila’s “Be Aware” strategy for using the Witness to navigate difficult moments during challenging conversations, when you are feeling (for example) uncomfortable, defensive, panicked, ashamed, or frozen. (Download a PDF of the graphic HERE.) As you read through it, consider these questions:

- What is your “gut reaction” to this model? Is it similar to other strategies for navigating difficult moments in conversation that you have learned or developed? What’s new or different about this? Do you feel resistant to any part of this method? Why do you think that is?

- Does this feel like something that is feasible or even possible for you to put into practice? Why or why not? What would be most challenging about this for you, and how might you address that challenge?

Here are a couple other mindfulness resources that may be helpful to get started:

If you like this content and want more, follow us on social media and subscribe to our listserv.