Note on the Use of “Decolonization”

In calling this reading series “Decolonizing Dialogue,” I wanted to highlight, as I stated in the series’ inaugural post, both the potential role of dialogue in decolonization and the ways in which we might decolonize our dialogue practices themselves. Like I also said in that first post, I’m not an expert in these topics — this reading series exists to make some of my own learning process visible and accessible to others, as I think my way through a few texts focused on anti-oppression approaches to teaching and learning.

Here is more of that ongoing learning process. Through an account called @dineaesthetics and its creator charlie / amáyá, I became aware of the frustration felt by many Native and Indigenous activists and scholars at the use of “decolonization” as a buzzword that has become detached from literal efforts to restore Indigenous lands, resources, and peoples. In this post, charlie / amáyá links to an article called “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor” by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang. In this article, Tuck and Yang point out that educators have with increasing frequency chosen to replace the vocabulary of critical, anti-racist, or social justice pedagogy with the word “decolonization” (or consider it to be synonymous). Tuck and Yang locate the persistent (mis)use of “decolonization” as a metaphor within “a long and bumbled history of non-Indigenous peoples making moves to alleviate the impacts of colonization” (3).

It’s important to acknowledge and clarify that in this series, I have absolutely been referring to a kind of cultural or ideological decolonization based on the de-centering of White/Western colonial perspectives and paradigms (rather than focusing on the literal restoration of colonized lands and resources to the peoples from whom they were taken). I’ve taken up the term from educators like Chavez who speak of decolonizing the classroom, works like Decolonising the Mind by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, and movements like “Decolonize Your Bookshelf.” I’ve been using “decoloniality” to signify a methodology or an approach to teaching and knowledge construction that resists a colonialist ethos of domination, control, hierarchy, and competition, following this definition I’ve linked before in the series.

I’m very grateful to charlie / amáyá of @dineaesthetics as well as to Tuck and Yang for making me aware of this tension. It’s clear to me that I need to keep thinking, carefully, about what exactly I and others mean by “decolonization” and “decoloniality” and who is and is not served by the varying use of these terms. Going forward, I’ll pull back from using the word “decolonize” and be more careful about collapsing anti-oppression terms together, while continuing to explore the value that various anti-oppression movements can add to our dialogues (and vice versa).

Overview of Stop Talking

As it happens, the work I’m focusing on this week is Stop Talking: Indigenous Ways of Teaching and Learning and Difficult Dialogues in Higher Education by Ilarion (Larry) Merculieff and Libby Roderick (2013). First author Ilarion (Larry) Merculieff, Aleut, is an Alaska Native Community Leader and Consultant, while second author Libby Roderick is Associate Director of the Center for Advancing Faculty Excellence at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

This book comes out of a weeklong faculty intensive organized through a partnership between Alaska Native educators, Elders, and community members and two Anchorage, Alaska-based public universities: University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA) and Alaska Pacific University (APU). The book is a follow-up to 2008’s Start Talking: A Handbook for Engaging Difficult Dialogues in Higher Education, edited by Kay Landis. Both Start Talking and Stop Talking are available as open-access PDF downloads.

The structure of Stop Talking mimics the programming of the five-day faculty intensive and reproduces much of its content, in order to give the reader something of the experience of participating and learning alongside non-Native faculty members and the Alaska Native Elders, educators, community leaders, and performers who served as their guides and leaders. The book quite clearly assumes a reader who is non-Native and may be from any academic discipline. The chapters are based around short written essays and transcripts of oral stories, performances, conversations, and talks that represent the direct voice of the Indigenous participants. They speak mainly to Indigenous ways of learning, teaching, and being and challenges that Indigenous students face in traditional Western education structures.

In Stop Talking, the authors eschew the term “decolonizing” to describe the approaches they are advocating and instead use “indigenizing.” Indigenizing education, they explain, means “infusing indigenous values and perspectives into every aspect of higher education. . . . We don’t mean incorporating small features of them into the status quo, nor do we necessarily mean replacing traditional Western approaches with indigenous ones. We mean giving equal credence to and having the flexibility to draw from indigenous approaches as appropriate. Indigenizing education means that indigenous approaches are seen as normal, central, and useful, rather than archaic, exotic, alternative, or otherwise marginal” (41-42).

Major Concepts: Listening; Place-Based Learning; Affirmation; and Storytelling

Here are some of the anchoring concepts from Stop Talking. For each one, I’ve suggested a few questions, inviting you to dialogue with these ideas through the lens of your own values, experiences, and goals.

Listening. The title of the book, Stop Talking, refers to the importance of cultivating presence, stillness, and receptivity, in contrast to the Western imperative to respond quickly, talk at length, and assert whatever authority one can claim. The authors write, “There is a distinctive rhythm to indigenous discourse. The pace is deliberately slow, and there are lots of pauses and silences. No one interrupts or talks over another. Traditional listening is an active process of consciousness, awareness, and attention that begins with mutual respect for and from each individual in the exchange. Listeners quiet their minds, give the speaker their full attention, listen without agenda, and take in as fully as possible each speaker’s unique truth. As each speaker finishes, there is a pause for silence and reflection” (22).

- How would you describe the rhythm and customs of typical classroom or community discussions you are a part of? How satisfying are those conversations to you?

- How would you describe your own listening style? What aspects of the kind of listening valued in Stop Talking are appealing to you?

- How could you practice this kind of listening? What would be the pitfalls or challenges of trying to practice the Indigenous style of discourse described above? How might you address those?

Place-based Learning. Elder Elsie Mather, Yup’ik, says, in a conversation with other Elders, “In a way, it’s sad that we are becoming so dependent on reading for information. You and a book — you can closet yourself anywhere and learn (or not learn, depending on the quality of your reading material). You can be thousands of miles away from your source of information. When you have that book, it doesn’t matter where your learning takes place. . . . This dependency on books. I call it a monster because of the distance it puts between us and our sources” (57). The authors of Stop Talking emphasize that one essential way to Indigenize learning is to complement “book-learning” with place-based teaching and learning. Place-based knowledge, Merculieff and Roderick explain, “springs from a deep and detailed experience of a place and manifests as a sense of belonging to, identification with, and awareness of everything that goes on in that place” (19).

- How much of your learning — in each subject you are currently studying — is grounded in local history, culture, people, and current events? What might it add to each of those subjects to include more place-based elements?

- What are ways we might come closer to the source of knowledge (even and especially if the content of our studies is based on sites and peoples that are geographically or historically far away)? Think beyond scholarly methodologies to consider ways to connect to people, art, music, stories, artifacts, and environments across time and space.

- How might you bring a place-based ethos to dialogue?

Affirmation. Educator Ilarion (Larry) Merculieff, Aleut, writes: “Whenever I passed an adult, I would hear ‘aang laakaiyaax, exumnaakotxtxin. Hello young boy. You are good.’ I was never rejected, never judged, never criticized, always and only positively affirmed by everyone in my village nearly every day of my entire childhood. Can you imagine what that’s like, how beautiful that is?” (60). Throughout Stop Talking, the need to cultivate strong relationships between students and teachers through affirmation comes up again and again. Though it is something that the Native educators cited above speak about in the context of children receiving loving affirmation from adults, it transfers to university-level settings. It challenges the traditional Western view of the teacher as an evaluator, a grader, and a corrector and reframes the teacher as a nurturer. The authors explain, “Most indigenous Elders and teachers offer little, if any, direct verbal feedback to correct performance errors. According to traditional understanding, you risk diminishing a human being by giving specific instructions” (21).

- What is your reaction to these ideas? Where do you think that reaction comes from?

- What kinds of feedback from teachers and other mentors do you find most helpful? When you are in the role of mentor or guide, what kinds of feedback do you strive to give? Do you relate to what is described of Alaska Native students and educators above, or is this very different from your own preferences and priorities?

- What do you think students’ responsibilities are with regards to affirming one another during dialogue? What is the teacher’s responsibility with regards to affirming students?

Storytelling. The authors of Stop Talking emphasize “the embodied, direct, oral and visual style of learning common to most indigenous cultures” throughout the book (4). One of the book’s authors, Ilarion (Larry) Merculieff, Aleut, particularly stresses the value of storytelling in Indigenous approaches to teaching and learning: “Stories allow the teller to express whatever is most important and give listeners the latitude to take away whatever they are able to see or learn. Each person sees and learns different things from the same story. The story does not dictate the lesson to be learned; rather it creates the opportunity to learn whatever the individual is capable of learning. If I give you a direct answer, there’s no freedom. I am acting as the authority, the expert. But in the relationship between real human beings there is no one-upmanship. I am not the answer. I don’t know any more than you do. The only difference between us is our experience and how we use our inherent intelligence” (59).

- How much of your formal education (in school or religious education contexts) and informal education (at home, among family, or in the community) has included storytelling? What stories come to mind, if any, when you think about these teachings?

- What place might storytelling have in your studies or community-based work? How might it enrich or add meaning to your discipline, even and especially if you consider your field to be very fact-based, data-driven, or objective?

- What do you think is the role of storytelling in dialogue?

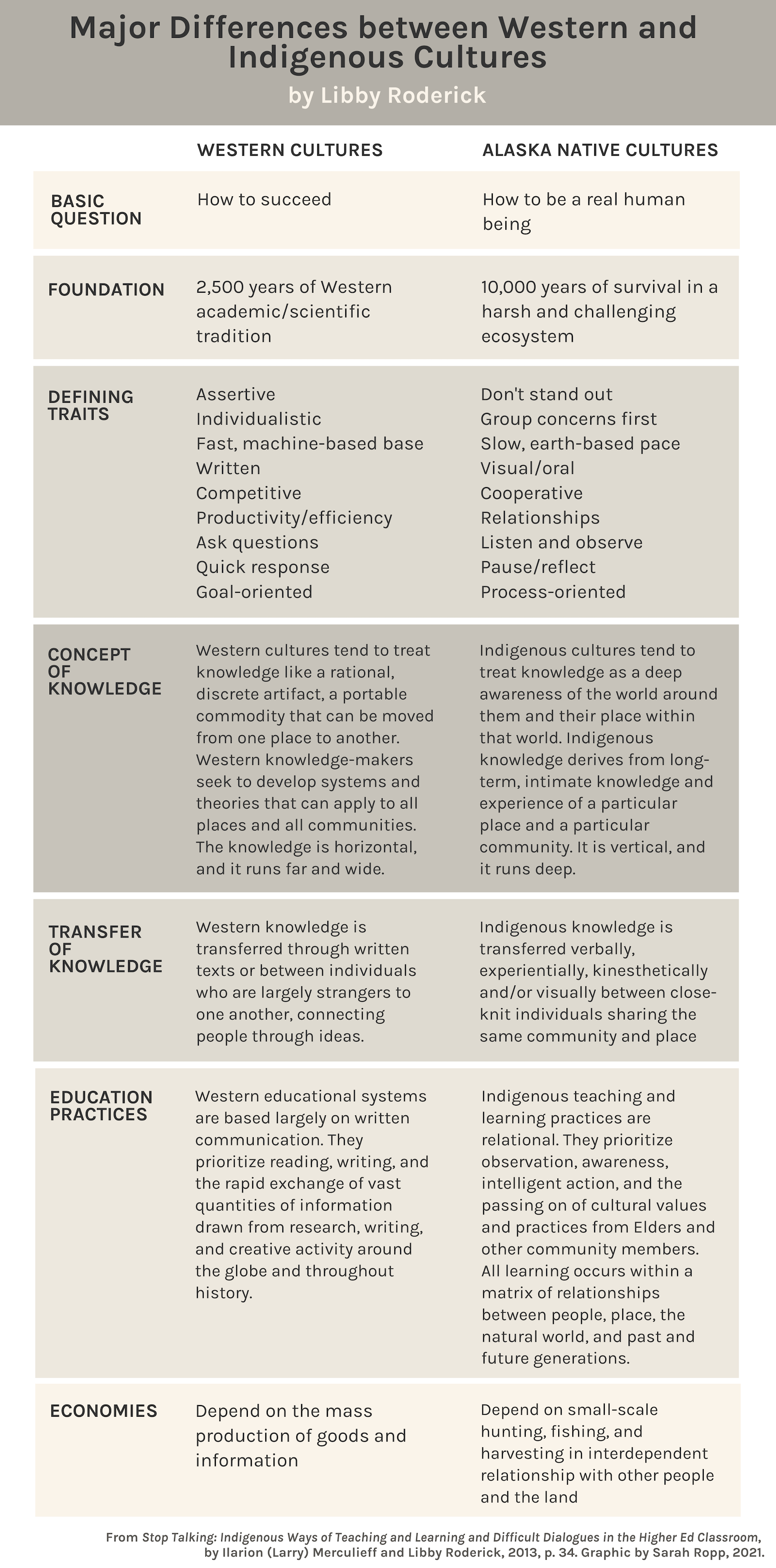

Finally, from page 34 of Stop Talking, below is a graphic summarizing some of the core differences between Western academic cultures and Alaska Native cultures. Click to download a PDF of this graphic, or access the plain-text version in the free online version of Stop Talking.