Overview of The Art of Communicating

This week, I’m reading The Art of Communicating by Thích Nhất Hạnh.

(For an introduction to this blog series on anti-oppression approaches to dialogue, see here; for other entries in the series, see “Sarah’s Content” on this page.)

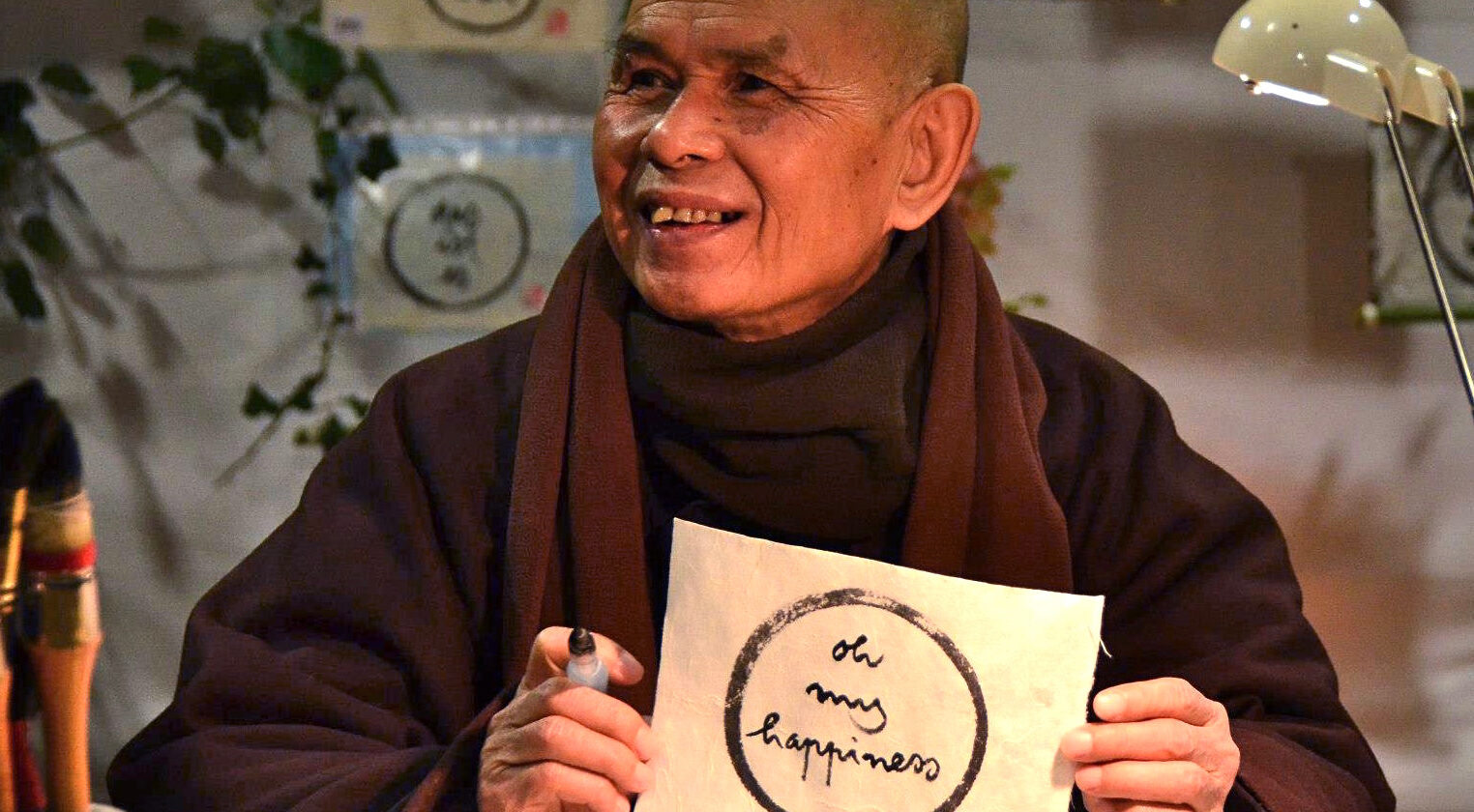

Thích Nhất Hạnh, born 1926 in Vietnam, is a Zen Master Buddhist monk who is credited with renewing Vietnamese Buddhism, introducing mindfulness to the West, and founding the Engaged Buddhism movement. This movement, which Hanh was inspired to create during the Vietnam War, places equal emphasis on contemplative practice for internal transformation and efforts to alleviate the suffering of others. For his involvement in pacifist activism against the war in the U.S. and Europe in 1966, Hanh was barred from returning to Vietnam, an exile that lasted four decades. He is the author of over 100 books in English and has founded a university, a foundation, a publishing house, a peace activist magazine, and a number of monasteries.

The Art of Communicating, which you can listen to in full on YouTube, starts from the premise that no communication is ever neutral. Every communication we put out into the world and every communication we take in from others has the potential to nourish, ease suffering, and create peace or to poison, increase suffering, and create violence. This includes not just our words, but also our body language, nonverbal sounds, facial expressions, and so on — even the energy generated by our thoughts and emotions that is available to be absorbed and interpreted by others. Thích Nhất Hạnh advocates for a radically mindful approach to communication that practices deep connection to the self and the earth as the means by which compassion for self and other is able to develop. Compassion, he proposes, is the key to both deep listening and “right speech,” and “the one goal of compassionate communication is to help others suffer less” (39).

Hanh focuses on interpersonal communication between family members, partners, and friends as well as workplace and community or activist contexts. Though he doesn’t precisely address classroom contexts, it is a recurring suggestion throughout The Art of Communicating that to speak and to share one’s truth is to teach; we are all, as communicators, always already teachers and students. I believe Hanh’s work is decolonial (see this post for clarification regarding my use of this term) not just in that it is grounded in an Eastern spiritual tradition, but also in that he advocates for a community-focused ethos of peaceful, non-competitive communication and in that he reframes what it means to be “a teacher” in a way that resists hierarchy, domination, and authority.

Major Concepts: Self-Compassion; Mindful Listening; Right Speech; and Communication as Continuation

Here are some of the anchoring concepts from The Art of Communicating. For each one, I’ve suggested a few questions, inviting you to dialogue with these ideas through the lens of your own values, experiences, and goals.

Self-Compassion. Thích Nhất Hạnh stresses that love for the self is essential in order to cultivate the compassion for others that will enable deep listening. He argues that we are each our own one true home, and defines home as “the place where loneliness disappears. When we’re home, we feel warm, comfortable, safe, fulfilled” (17). Coming back home to ourselves, he writes, begins with mindfulness, in particular paying attention to one’s breathing in order to become present in the body, present with the earth, and present in the moment. This awareness is liberating, allowing us to recognize, accept, befriend, and finally release our pain, our anger, and our suffering. “These feelings are like a small child tugging at our sleeves,” he writes. “Pick them up and hold them tenderly. Acknowledging our feelings without judging them or pushing them away, embracing them with mindfulness, is an act of homecoming” (28). In learning to be gentle with our own feelings, we learn to be more gentle with the feelings of others and to help them come home to themselves, too.

- What is your reaction to this notion of the self as home? Do you feel at home with yourself? In what spaces and situations do you feel most at home in your own body? In what spaces and situations do you feel least at home in your own body?

- How frequently do feelings of anger, frustration, sadness, shame, anxiety, or other forms of pain occur for you in the classrooms, community spaces, and workplaces you’re a part of? What tends to produce those feelings? How do you generally handle them?

Mindful Listening. Deep listening is one of the two keys Hanh identifies for compassionate communication (the other is loving speech, explained below). Mindfulness of several kinds simultaneously is the foundational component of deep listening. Firstly, Hanh writes, we must remain humbly aware that our own misperceptions and our suffering are never fully resolved and are the filter through which we receive and transmit all our communication. Secondly, he suggests, we must remind ourselves that there is a “Buddha” inside every person, “a name for the most understanding and compassionate person it’s possible to be” (40). Even or especially when the other person is not behaving in a loving or respectful way, Hanh says, you must listen and speak to that person with respect for the Buddha that resides (possibly very deep) inside them. Doing so helps the Buddha within to come out. As such, to perform a gesture of respect at the start of a conversation with a difficult person (Hanh uses the example of bowing) is “a practice of awakening” for both oneself and the other (40). And finally, mindfulness in listening is also about striving to become aware of the other’s suffering as they are speaking. To do this, Hanh explains, one must practice deep breathing while listening without interrupting, correcting, or judging the other person. He emphasizes that it is perfectly okay to not be ready to listen in this way, to attend to one’s own anger, irritation, or pain before attempting to offer this kind of compassionate listening.

- What is your reaction to the notion of a “Buddha” inside each person? Does this align in any way with teachings you have absorbed (implicitly or explicitly) in your own family, cultural, or faith traditions? Can you imagine applying this concept to the difficult people you encounter in your life — in class, at work, or in community spaces?

- What about the notion that the point of communication is the mutual relief of suffering? Does this understanding of dialogue as (the path to) wellness resonate with you or do you understand the purpose of dialogue (and the meaning of wellness) to be something different?

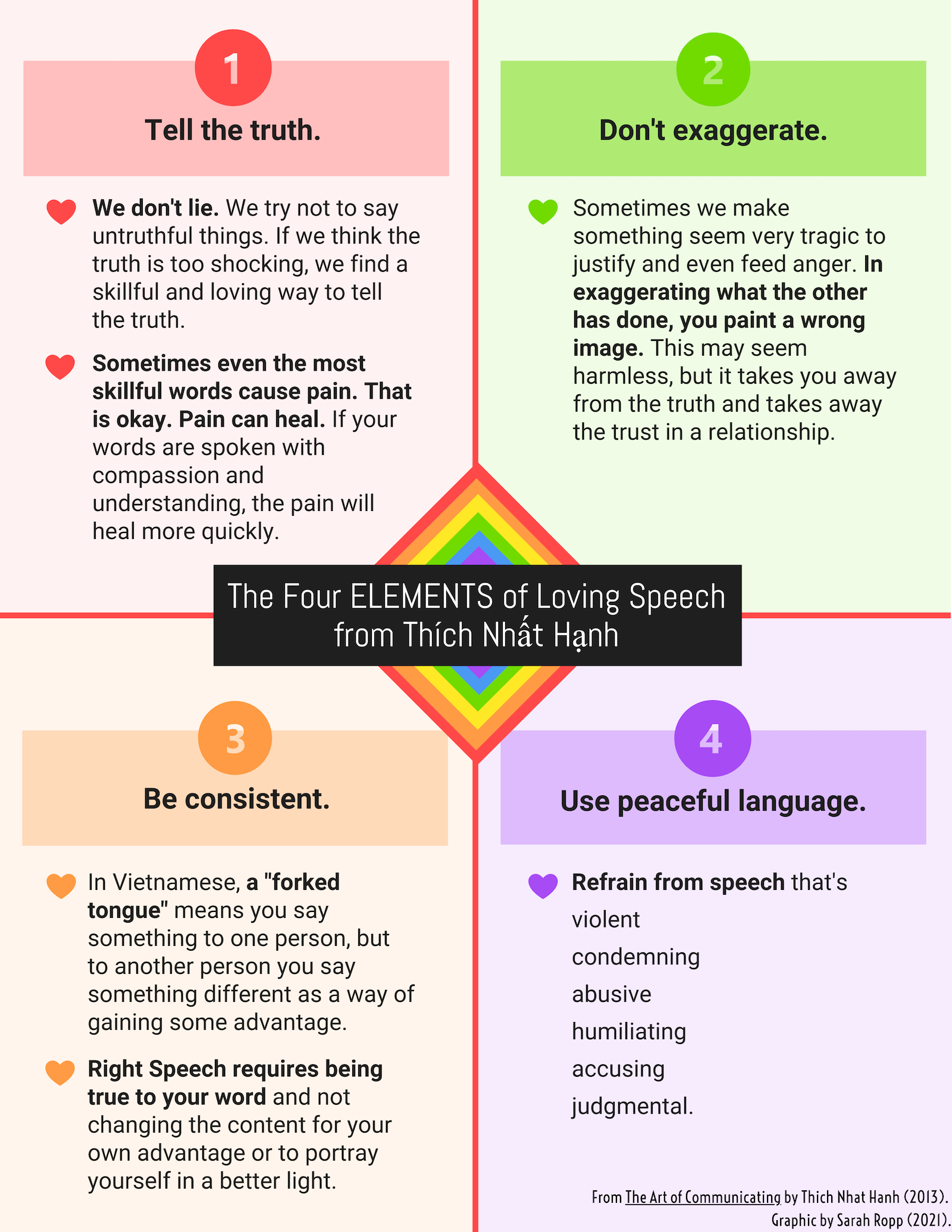

Right Speech. Thích Nhất Hạnh explains that “Right Speech” is a Buddhist term for loving speech, or speech that is nourishing, peaceful, compassionate, and understanding in contrast to “wrong speech” — “the kind of speech that lacks openness and does not have understanding, compassion, and reconciliation at its base” (51). In the Buddhist tradition, Hanh explains, Right Speech is so important that four out of Ten Bodhisattva Trainings address guidelines for loving communication (a bodhisattva, meanwhile, is “an enlightened being who has dedicated [their] life to alleviating the suffering of all living beings” (52)). The interrelated graphics below present the Four Elements of Loving Speech, or the practices of Right Speech, and the Four Criteria of Loving Speech, or the means by which to assess whether or not one’s speech is Right. Click to download a PDF of both graphics. As you consider the Four Elements and Four Criteria of Loving Speech, you’re invited to reflect on the following:

- Which of the four elements comes most easily for you or do you feel particularly strongly about? Which is most challenging for you? Do you feel pushback or resistance to any of these elements? Why or why not?

- Considering the four criteria: is it meaningful for you in any way to consider communication as teaching or to consider yourself as a “teacher” each time you offer your observations, experiences, and beliefs to others? Have you had “teachers” (whether in the formal, traditional sense or in the more broad, universal sense that Hanh uses the term) that were particularly skilled according to these criteria? What was the impact for you? In your assessment of yourself as a teacher-communicator, which of these criteria strikes you as most challenging, important, or transformative?

Communication as Continuation. “Our communication is what we put out into the world and what remains after we have left it,” Hanh writes. He explains that we are constantly communicating — with ourselves, with other humans and other animals, and with our environments — and explains that we produce three main forms of energy: thought, speech, and action. Each of these energies both is, and is interconnected with, communication. Because thought produces energy and affects both speech and bodily action, thought is action; it is also communication with the self. Action as we commonly think of it — discernible action that produces some form of change — is, in turn, both a manifestation of thought and a form of speech. The Sanskrit word karma means “action” and refers to this triple set of actions (139). The communication that all of these different forms of action represent is our imprint on the world: “Everything we do and say bears our signature,” Hanh says. “Our communications will not be lost when our physical bodies are no longer here. The effect of our thinking, speech, and physical actions will continue to ripple outward into the cosmos” (142-43). He emphasizes that loving speech and deep listening have the power to allow us to “continue beautifully into the future” through these ripple effects (143). At the same time, compassionate communication has the power to reach back through time and heal the suffering of the past. We carry our parents and ancestors — and their suffering, and their joy — in our cells. If we can heal ourselves through offering and receiving compassion, Hanh says, we are also healing past generations. This is communication-as-continuation that extends, non-linearly, both forwards and backwards, rooted in, but branching beyond, the self.

- What is your response to the idea that all of our communications bear our signature and persist in impact beyond the moment of utterance? Are there particular moments of communication you have received from others that persist in affecting you (whether positively or negatively)? Are you aware of any words you have uttered that persist in affecting someone else (whether positively or negatively)?

- What is your response to the idea of healing ancestral and parental wounds through loving communication with the self and others? Do you believe in this as a possibility? What wounds would you hope to heal in the past and/or the future?

If you like this content and want more, follow us on social media and subscribe to our listserv.