“Decolonizing Dialogue” Series Wrap-Up + Resources

This week, I’m reading We Want to Do More than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom by Bettina L. Love.

Before I get into Love’s book, a note: This is the final post in this semester’s “Decolonizing Dialogue” series! I have loved publicly exploring dialogue, anti-oppression efforts in and beyond education, and the relationships between the two via this blog medium. I thank you, the reader, as well as the authors of these 8 rich and thought-provoking texts for sharing their thinking and methods. I will be drawing on them as I teach my COMM 290 course “Good Talk” next semester here at Penn.

For the sake of having all the posts accessible from one place, here are links to the other 7 posts in the series:

- Paulo Freire and Dialogue as “Existential Necessity” for Liberation

- Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence by Derald Wing Sue

- Moving Mindfully through Difficult Dialogues with Beth Berila

- The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop by Felicia Rose Chavez

- Stop Talking by Ilarion Merculieff and Libby Roderick

- Inclusive Freedom as a Framework for Campus Speech by Sigal Ben-Porath

- Thich Nhat Hanh: “Our Communication Is Our Continuation”

If you enjoyed this series, check out more of my public-facing writing on dialogic pedagogies at Thinking In Community, the official blog of the Humanities Institute at the University of Texas at Austin, at this link: https://sites.utexas.edu/humanitiesinstitute/?s=Sarah+Ropp

Finally, see my website for open-access downloadable resources related to dialogue: sarahropp.com/resources-for-dialogue/. This page collects all of the graphics I’ve created for this series as well as other original graphics, activities, and ideas related to dialogue. I update it regularly with new resources, and all are free for anyone who would like to use them.

Overview of We Want to Do More than Survive

Bettina L. Love is the Georgia Athletic Association Endowed Professor in Education at the University of Georgia. She is the cofounder of the Abolitionist Teaching Network and the creator of Get Free, a hip-hop civics curriculum. Her work is informed by critical pedagogy, critical race theory, and Black feminism, and she has won a number of awards for her scholarship, teaching, and advocacy efforts related to anti-racist educational reform.

We Want to Do More than Survive, published in 2019, is Love’s second book, following 2012’s Hip Hop’s Li’l Sistas Speak: Negotiating Hip-Hop Identities and Politics in the New South. In We Want to Do More than Survive, Love argues for a pedagogy that actively works towards radically restructuring and reimagining the prevailing educational model in the U.S. This pedagogy, which Love calls “abolitionist teaching,” is devoted to intersectional racial justice in and beyond the classroom through civics education, community coalition building, and critical theory. She refers to recent high-profile events and activism related to racial injustice; academic research in education; abolitionist histories; critical theory; and her own experiences as a Black, queer, female student and educator to make this argument.

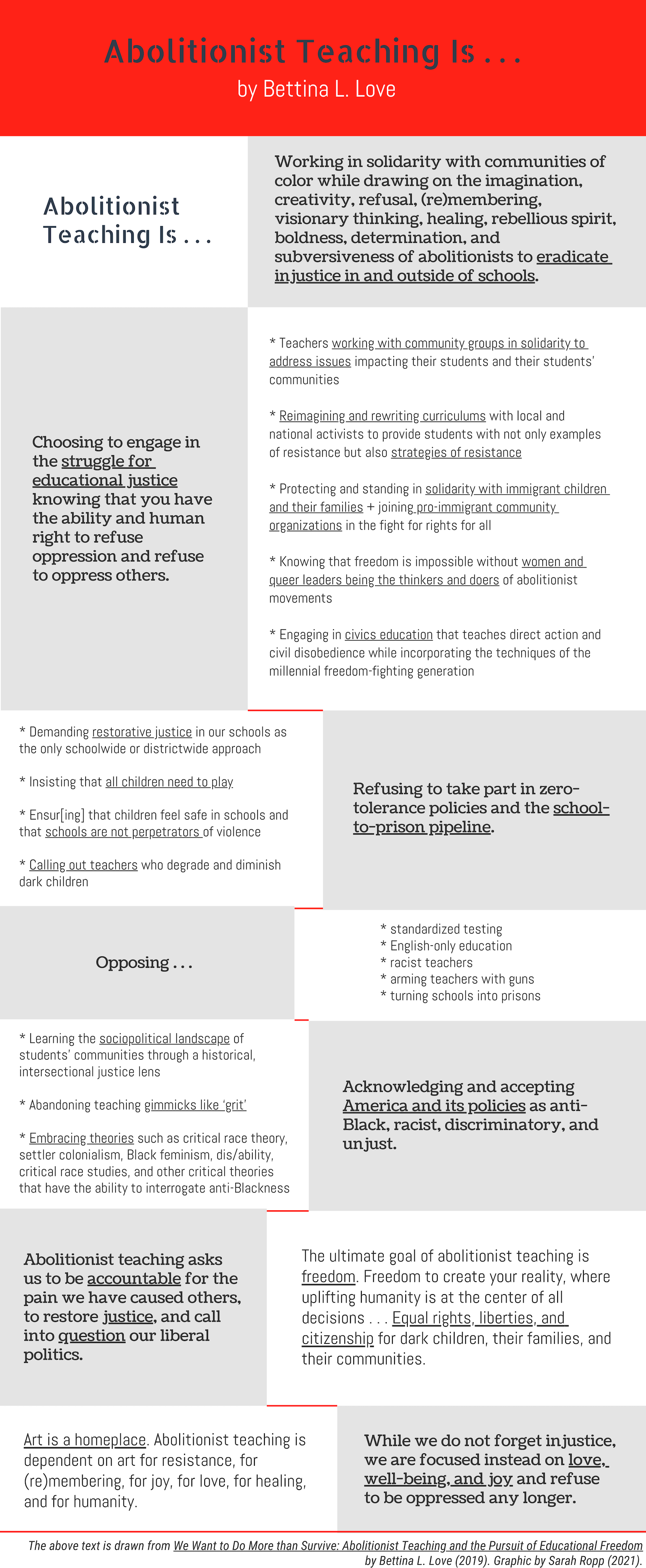

The graphic below presents, in Love’s own words, some of the core principles of abolitionist teaching. (Access a plain-text version here: Abolitionist Teaching Principles plain-text version. Download a PDF of the graphic here: Abolitionist Teaching Principles PDF.)

Major Concepts: Educational Survival Complex; Character Education; Freedom Dreaming; and Homeplace

Here are some of the anchoring concepts from We Want to Do More than Survive. For each one, I’ve suggested a few questions, inviting you to dialogue with these ideas through the lens of your own values, experiences, and goals.

Educational Survival Complex. Love characterizes the prevailing educational system in the U.S. as an “educational survival complex, in which students are left learning to merely survive” in schools that mimic and reproduce the same inherently inequitable and oppressive structures of the larger society (27). Those structures include the punitive logics of the carceral justice system; the competitive, production-driven logics of neoliberal capitalism; and the conformity-driven logics of cisheteropatriarchy — among others. Students of color or what Love calls “dark children,” as well as poor children, suffer disproportionately and extremely within the educational survival complex, but it is, Love argues, an inherently damaging system for all. Privatization and profiteering, through the proliferation of charter schools and the corporations that sell standardized tests, capitalize on the dreams of dark-skinned and poor communities to “do more than survive” — i.e., to use education as a vehicle for economic advancement and liberation. Just as damaging, Love suggests, is the “spirit murder” that occurs when teachers and administrators degrade and dehumanize their students of color on a daily basis through (for example) discriminatory discipline practices, the ridicule or erasure of non-White cultures and language varieties, and low expectations for academic performance. Such constant degradation keeps “the spirit enduring in constant survival mode” and “is violence by another name” (33).

- What is your response to the concept of the educational survival complex? Does this align with your experiences as a student (K-12 and/or college)? In general, do you believe your education has encouraged you to survive or to thrive, neither, or both?

- In regards to the concept of spirit murder: what state is your spirit currently in? Thinking of the classroom, the workplace, and/or the community spaces you operate within, what practices and mechanisms help your spirit thrive and feel strong? What practices and mechanisms batter your spirit?

Character Education. A defining feature of the educational survival complex, Love says, is its growing emphasis on “character education” over civics education. That is, in this highly individualistic system, students are encouraged to develop the individual character traits that will (supposedly) help them overcome any and all disadvantages in their pathway through education, rather than encouraged to critique and challenge systems of inequality. This is the fanatic focus on cultivating “grit,” the no-excuses ethos, and the “work hard, be nice” mantra. Efforts to first instill and then measure and assess grit among poor and dark students have a direct link to a long history of “good” White people in the U.S. attempting to reshape the supposedly inadequate moral character of people of color in order to help them conform and survive — rather than abolishing the structures that make their survival so difficult in the first place. This history includes (for example) the Christianization of enslaved people, Indian boarding schools, and prohibitions against speaking Spanish at school. While Love acknowledges that grit, resilience, and hard work are positive traits for students to possess, she rejects the way in which character education has displaced civics education in schools. Instead of this hyper-focus on exceptionalism and the individual’s power to miraculously overcome structural barriers, she suggests that we must work towards closing the “civics empowerment gap” by educating students in media literacy and how to become informed, active citizens through practices such as petitioning, protesting, public speaking, problem-solving across difference, and civil disobedience (70).

- What was civics education like in the schools you have attended (K-12 and college)? Do you, in general, feel empowered to engage in change-making efforts such as the ones Love lists? Why or why not?

- What kind of character education has been promoted in the educational settings and/or community settings you operate within? Are you familiar with the discourse and history of “grit,” “no excuses,” or “work hard, be nice”? What has been the impact on you of the kinds of character education you were (or weren’t) exposed to?

Homeplace. Throughout We Want to Do More than Survive, Love emphasizes the vital importance of homeplace for students, especially dark and poor students. In critical contrast to the individualism, spirit murder, and competitive character education of the educational survival complex, the concept of homeplace stresses the importance of community, affirmation, and safety for learning. A notion from bell hooks, Love explains, “‘homeplace’ is a space where Black folx truly matter to each other, where souls are nurtured, comforted, and fed. Homeplace is a community, typically led by women, where White power and the damages done by it are healed by loving Blackness and restoring dignity” (83). Within homeplace, character components like grit, zest, and potential are not obsessively tracked and measured so much as an environment is created within which these traits — which dark and poor kids already possess — can be protected and nurtured (79). Love describes how, for her, the homeplace that allowed her spirit to remain intact through struggles with poverty and her parents’ addiction was created through a network of supportive adults and peers — including teachers, coaches, mentors, and older students — a constellation of community centers and youth activist organizations, and joyful engagement with Black cultural elements like music and basketball.

- How do you respond to this notion of “homeplace” and its importance within educational spaces? Regardless of your identities, when have you experienced your own form of “homeplace” in your school(s) or community(ies)? What made homeplace possible or impossible for you in these spaces?

- What are our responsibilities to each other regarding homeplace? That is: how might you be able to contribute to (or at least avoid destroying) other students’ homeplaces?

Freedom Dreaming. “Freedom dreaming is imagining worlds that are just, representing people’s full humanity, centering people left on the edges, thriving in solidarity with folx from different identities who have struggled together for justice, and knowing that dreams are just around the corner with the might of people power” (103). In Love’s formulation, freedom dreaming is the beginning of abolitionist teaching; she insists, “These dreams are not whimsical, unattainable daydreams, they are critical and imaginative dreams of collective resistance” (101). She argues that this dogged power and will to continue to imagine new futures and alternate ways of being is the same power that has created and sustained every abolitionist and anti-oppression movement throughout history. If the educational survival complex aims to shut down freedom dreaming or repackage it as neo-liberal aspirations of individual wealth and advancement within an un-critiqued system, truly abolitionist teaching and learning insists on the importance of fostering freedom dreams. Love explains that freedom dreaming both supports and is supported by Black joy, love, and wellness as well as art in its many forms.

- What does freedom dreaming look like for you? That is, how would you define “liberation” for yourself personally as well as for the people from your various communities? What kinds of art or inspiration helps you to engage in freedom dreaming?

- In what way does, or can, dialogue support freedom dreaming? Have you been a part of dialogues that are about collective freedom dreaming or the sharing of freedom dreams? If so, what was that experience like? If not, what do you imagine it might be like?

If you like this content and want more, follow us on social media and subscribe to our listserv.