Our friends, of course, remain of interest to us. We care about how and what they are doing, their health and their family’s. We chat with them about current events, the shows we are binging, how our favorite teams are doing. And even when we do disagree, we are likely to be interested in their thinking and they in ours.

Principle 4: Redefine the win

Valuing those with whom you disagree

But what about the “familiar stranger” – someone who sits in the same class or office as we do, stands along the same soccer sideline, gets coffee at the same Wawa at the same time as us, or shows up at the same social events?

We don’t know their families, their history, how they spend their days, what media they consume. Or how they think about current events – local, national, or international.

Talking about such things with such a nodding acquaintance might be interesting, perhaps even rewarding. It can also be fraught. After all, what if we disagree? How will we handle that? In modern-day America, we have all seen or experienced plenty of experiences of such conservations going awry. We know instances where people suffered painful consequences for “saying the wrong thing.” Thus, even the possibility of conversation may induce anxiety or reluctance.

Things become even more problematic when we consider that our self-esteem and identity can be at stake in any conversation, particularly those Stone et. al call “difficult conversations.”[1] We feel we have to “hold our own,” to defend our identities, ideas, beliefs, and values.

The prospect becomes even more fraught when we suspect or know that the other person holds different opinions, perspectives, or positions from ours. Many people today walk around with emblems of their political views on their clothes, their hats, their laptops, their cars – a signal we may take as reason to steer clear of any talk that goes beyond the weather or the Eagles game.

Beyond that, most of us have an aunt, uncle, sibling, or parent with whom we have long found civil conversation about specific topics to be difficult if not impossible. There, we pretty much “know” we’ll disagree, producing heated or wounding words.

So once again, we adopt the strictly weather-sports-how’s-the-family conversational strategy.

Stable democracies require an open exchange of valid information

This raises a big question, a very practical one: “What’s the point of even bothering to engage with these others? Isn’t it just smart to avoid talking about politics or controversial issues? What possible benefit could there be to attempt these risky conversations?”

The answer: It perhaps is smart in terms of one’s blood pressure. But it’s clearly less good for very health and stability of our democratic republic is at stake.

Here’s why: Americans are increasingly segregating themselves in terms of political and cultural values. In some towns, it can be hard even to run across folks who vote differently from you. If, when you do chance upon someone of different views, you rigorously avoid any meaningful conversation, how will you ever get any accurate information about why other people think, vote and express values differently from you? And how will they ever gain the same about you?

Breaking down misinformation of partisan media

This void of information then is ripe for being filled by misinformation and negative stereotypes peddled by partisan media of all stripes.

One of our biggest challenges in this democracy has become: My idea of you and your idea of me.

If you’ve never knowingly met and chatted with a Biden voter, it’s easier to believe the malignant Stop the Steal lies. If you’ve never met and chatted with a responsible gun own and hunter who doesn’t hew to absolutist gun rights rhetoric, you’ll just assume the NRA speaks for millions more than it really does.

So, if you agree that, as a patriotic and personally useful act, we should try harder to have those difficult conversations, then the second question arises: “How do we do it?” This series of posts lay out six overarching principles and nine specific, practical ground rules to help you figure that out.

God knows, we don’t seem to have many good public models about how to conduct good conversations on difficult topics.

What we see most commonly on TV is enlightening only in showing exactly what not to do.

On the “talking head” shows the goal clearly to score debating points, the more partisan zing the better. Everyone is trying to prove how smart there and how evil or foolish the other side is.

Ad hominem attacks abound. Attempts to understand what others are saying, asking questions for clarity or even searching for possible common ground is rare. In fact, in these days of media silos, it’s increasingly rare for “the other side” to be physically present. It exists mostly in a few cherry-picked video clips, a straw man to be kicked and spat upon.

The guiding rule: Win at any cost.

And that “cost” may, indeed, be great: Our views of fellow Americans become poisoned.

Our willingness to do the hard work of discussion and compromise need to preserve our great national experiment in self-governance may disappear.

The trust and the sense of basic humanity among citizens, indispensable the health of our democratic republic, may be irreparably damaged. Each side may become ever more rigid in their thinking, ever less willing to engage productively with each other.

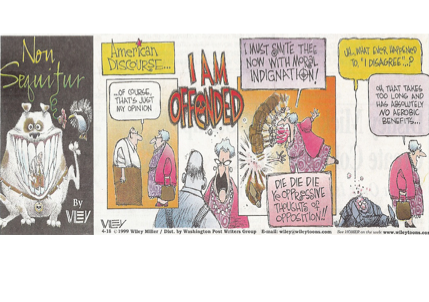

Too often such conversations can seem sadly reminiscent of this 1999 cartoon by Wiley:

Contrast this with the image of dialogue proposed by Daniel Yankelevich, the former “dean of public opinion polling” and cofounder of The Public Agenda Foundation[2]. Yankelevich offers two central and interdependent purposes of dialogue. The first is to develop mutual understanding and respect. The second is to jointly frame and solve problems. Our ability to do the latter depends on our ability to maintain the former.

Dialogue comes from two Greek roots: dia meaning “through” and logos meaning “word or meaning.” It is conversation in which people think together in working relationship – the relationship of fellow citizens. In a dialogue people talk not to win some competition, not to crush or “own” the other side, but to understand each other, perhaps even to understand why the other thinks it’s reasonable to think as they do. That mutual understanding and respect then become the foundation of problem solving.

As Yankelovich says, “Dialogue holds the key to creating greater cohesiveness among groups of Americans increasingly separated by differences in values, interests, status, politics, professional backgrounds, ethnicity, language, and convictions.” (The Magic of Dialogue, p. 31).

While he published those words in 2001, daily events, polls and studies demonstrate that the need for this kind of dialogue has only grown more urgent.[3]

Such mutual understanding and respect can be the basis of discovering “common ground,” [4] a reference to the “commons” originally found in most towns in America’s New England states.

Since colonial times, all in the town could use to use the commons graze the family livestock. It was land held and used in common, for the benefit of the entire community. But when some overused or abused the ground or failed to do their part to tend it, it ceased to be as useful to all. It became overgrazed and fallow. That development is known as the “tragedy of the commons” – one that in our society has become lamentably common.

It’s a rich metaphor for what happens when people focus mostly on individual comfort or gain and neglect the well-being of the community.

For when people define the win strictly in terms of their views and their interests dominating.

So how should we redefine the win when we attempt a difficult conversation?

Under the light of Yankelovich’s wisdom, we can ask: “Did I gain some understanding and respect for the other person? Did they gain the same about me? Did we both leave feeling we could continue the conversation, that we might even be able to work together on some shared problem some day?”

If you can answer yes to those three questions, then that conversation was a win. It was worth the risk of having it. It could pay dividends for you, the other person and our collective hope of saving our democracy.

This post is from a series of 6 principles and 9 ground rules for constructive dialogue developed and written by Chris Satullo and Harris Sokoloff for the SNF Paideia course: “Civil Dialogue Seminar: Civic Engagement in a Divided Nation”.

9 Ground Rules for Participating in Constructive Dialogue:

- Ground Rule 1 and 9: Listen, it’s as important as talking.

- Ground Rule 2: Everyone participates; no one dominates

- Ground Rule 3 and 4: Disagreement is fine. It’s fruitful. Don’t try to win it or paper it over. Explore it.

- Ground Rule 5: Build on what others say

- Ground Rule 6: Consider the possibility that, on any given issue, your information may be incomplete

- Ground Rule 7: Notice what voices are not in the room. Consider fairly what they might say if they were

- Ground Rule 8: Be honest, but never mean

6 Principles for Designing Constructive Dialogue:

- Principle 1: Design talk to lead to action

- Principle 2: A brave space

- Principle 3: If you want to hear a different conversation, you have to hold a different conversation

- Principle 4: Redefine the win

- Principle 5: Listen in the way you would like to be heard

- Principle 6: Begin with story not position

[1] For more on difficult conversations, see Stone, D., Patton, B., & Heen, S. Difficult conversations: How to discuss what matters most. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2010.

[2] Two of Yankelovich’s books are of particular interest here: Coming to Public Judgement: Making Democracy Work in A Complex World, Syracuse University Press, 1991 The Magic of Dialogue: Transforming Conflict into Cooperation, Simon & Schuster, 1999.

[3] Two interesting studies support this claim: More In Common’s Perception Gap and Pew Research Center report on the state of personal trust

[4] For a primer of promising practices for building common in community engagement Building Common Ground: Public Engagement, Promising Practices, Fels Research & Consulting Group, 2012