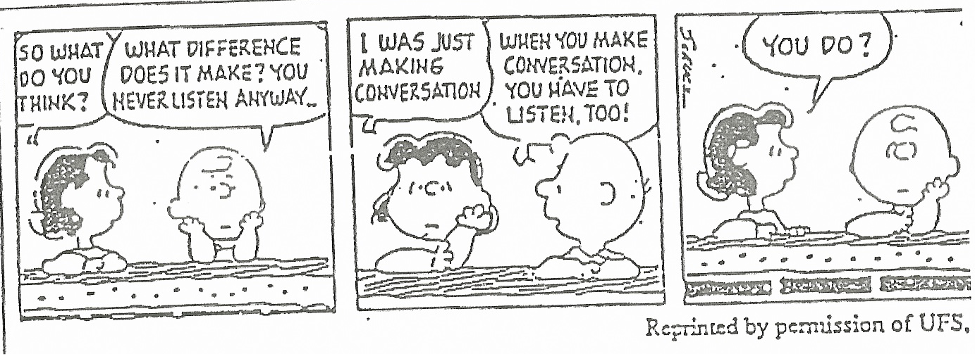

PRINCIPLE 5: Listen in the way you would like to be heard

Listen without distraction

Often during our casual conversations – or even our “deep ones” – we are multi-tasking or distracted. In fact, some of the research on conversations shows that we spend 10-15% of our time really listening, and the other 85-90% of our time thinking about/doing other things.

We are bombarded by sensory inputs that distract us: people walking by, background noise, the clothing of the person/people with whom we are talking.

Or perhaps we are still distracted by a previous conversation, or anticipating the next meeting, or thinking about something at home, or…. If we’re talking on the phone, we may be me checking email, or moving papers around, or some other task.

Avoid “confirmation bias”

Even when we spend a higher percentage of our energy listening, it may only be to figure out how we want to respond. Perhaps we listen only until we hear something that sounds like a topic sentence, then we set to work crafting a response or, worse, a rebuttal. But if you are like us, you don’t talk in topic sentences. In fact, it can take either of us a few sentences to get to our main point(s).

The way a person gets to the point can be as important as the point itself. It’s not just what he believes, but why – the experiences, the feelings, the sense of identity that lie beneath. When we indulge in what’s known as “selective” or “filtered” listening, we don’t seek for any of that. We listen with “confirmation bias” – just hunting evidence of what we already believe.

That could be something said that supports our position. Or it could be something that simply confirms our negative perception of the speaker – based either on experience or on negative stereotypes about race, class, gender, age, profession, political views, or mere appearance. Regardless, you are not really listening to this person, in this conversation, on this topic, at this time.

You are mostly listening to the noise in your own head.

And you definitely are not listening the way you yourself would like to be heard.

Qualities of good listening

Think for a moment about that: How we want others to listen to, and to hear, us.

First, we want to know that they are listening not just to our words, but what our words mean to us. Every word carries with it a denotation (a literal dictionary definition) and a range of connotations (a range of positive and negative associations words come to carry with them).

A word often connotes something different to different people.

So, listening to understand means asking the other person questions to clarify what they mean, rather than jumping to conclusions based on our assumptions and biases.

Secondly, understanding the connotations of words often requires going beneath the ideas expressed in the words to the feelings those words involve or evoke. This moves the conversation to deeper levels.

We are not just “thinking” beings; we also have feelings.

Those feelings are often in charge of our thoughts, far more than we recognize or acknowledge.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt uses a metaphor of “the rider and the elephant” – where the rider represents our rational/analytic side, and the elephant represents our emotional side. Sure, our thinking is important – it can choose a direction or path. But it’s the elephant, that powerful and sometimes hulking part of us, that energizes our will. It can often overpower the rider’s intentions.

Beneath others’ words, we must try to glimpse both the rider and the elephant if we want to understand what they meant and why they mean it.

As mentioned, our words- and our ability to grasp the words of others – get tied up in our identity – how we define ourselves and the groups to which we belong. Because our self-image and self-esteem are at stake in the identity part of the conversation, we want our words to be treated as though they matter.

We don’t necessarily want to be agreed with fully and all the time – at least we shouldn’t.

But we do desperately want what we say to be deemed worthy of consideration, a response – even if the response is disagreement.

So, when this principle recommends “Listen in the way you would wish to be heard,” that means trying to grasp not just the ideas but also the emotions and sense of identity that underlie a person’s meaning. It means listening as though what the other person says matters to you – that it connects somehow to your ideas, emotions, and identity.

Neighborhood Zoning

An example: One of us not long ago had a sidewalk conversation with a neighbor about a zoning issue in the neighborhood. Let him tell the tale …

A proposed new development on my street would take up half of a square block that is now a parking lot and fill it with a tall housing project offering minimal new parking. Some in the neighborhood, including me, are upset about how this project will cast dark shadows on their yards, harm gardens, cut down on views and make a parking crunch worse. As a devoted gardener, the effect on plants and flowers bothers me most.

The other person’s blasé attitude about the issue, the way he was indicating that my feelings as a gardener didn’t matter to him, was upsetting me.

But I realized I wasn’t really hearing him, either. I had to find out more about him to weigh what his response meant.

It turned out he’s a renter who expected to be moving within a year. He had little investment – monetary or emotional – in the block. The looming development to him was just part of living in a city – a complication he could easily move away from if it became bothersome.

We chatted some more, getting to know one another. By the time we said goodbye, we had some sense of connection. I felt he understood my viewpoint better and I was no longer mad at him for his.

We didn’t reach agreement, but we’d listened to one another as we wanted to be heard – and it had made a difference.

This post is from a series of 6 principles and 9 ground rules for constructive dialogue developed and written by Chris Satullo and Harris Sokoloff for the SNF Paideia course: “Civil Dialogue Seminar: Civic Engagement in a Divided Nation”.

9 Ground Rules for Participating in Constructive Dialogue:

- Ground Rule 1 and 9: Listen, it’s as important as talking.

- Ground Rule 2: Everyone participates; no one dominates

- Ground Rule 3 and 4: Disagreement is fine. It’s fruitful. Don’t try to win it or paper it over. Explore it.

- Ground Rule 5: Build on what others say

- Ground Rule 6: Consider the possibility that, on any given issue, your information may be incomplete

- Ground Rule 7: Notice what voices are not in the room. Consider fairly what they might say if they were

- Ground Rule 8: Be honest, but never mean

6 Principles for Designing Constructive Dialogue:

- Principle 1: Design talk to lead to action

- Principle 2: A brave space

- Principle 3: If you want to hear a different conversation, you have to hold a different conversation

- Principle 4: Redefine the win

- Principle 5: Listen in the way you would like to be heard

- Principle 6: Begin with story not position