On a May morning in 2018, Efrén C. Olivares walked into the most crowded courtroom that he had ever seen. He was in McAllen, a Texas town about seven miles north of Mexico, and the room was wall-to-wall, “jam-packed with men and women, all ages, who had been shackled, looking tired and sleep deprived, wearing clothes that had been worn for too long,” he said. There were no children. Olivares’ first task was to determine if any of these adults, immigrants charged with the misdemeanor of crossing the border, had been separated from their children. Then he sought to reunite the families.

Olivares, who graduated from Penn in 2005, is now deputy legal director of the Immigrant Justice Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center . During the 2022 Dolores Huerta keynote lecture, “Zero Tolerance: Journeys Through Family Separation and U.S. Immigration Policy,” he spoke about his personal and professional immigration experiences.

The Dolores Huerta lecture is the signature program of Penn’s celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month, said Krista Cortes, director of La Casa Latina, in her introduction. “This lecture is dedicated to the living political activist Dolores Huerta, who, in her 92 years of life, has given tirelessly of herself to improve the working conditions of farm workers and the civil rights of the working poor women and children.”

In that McAllen courtroom, everyone was confused, Olivares said. The people shackled and sitting on benches thought this was immigration court. But these were criminal proceedings. In 2018, the Trump administration initiated the zero-tolerance policy, which called for the prosecution of everyone that crossed the border.

That the immigrants were charged under a law that had been on the books since 1929, which said that crossing the border between ports of entry was a misdemeanor, with a maximum fine of $250 and as long as six months in prison. Immigrants are expected to plead “guilty” and get “time served,” Olivares said. They would then be transferred to immigration agencies and deported. But what about those traveling with children? What happened to them?

Once their parents were detained by Homeland Security, any minors would be considered “unaccompanied,” Olivares said. By the time the parents were processed, their children were gone.

The law “was explicitly designed or intended to deter and discourage future immigrants from coming by inflicting as much pain and suffering on those families,” Olivares said.

He noted stories he had gleaned from immigrants, many of whom were indigenous, speaking Spanish as a second language.

“Viviana from Guatemala was traveling north with her 11-year-old son,” said Olivares. Her husband had been murdered, she said, and now his killers were after her and her son. The son was placed in a South Texas shelter; she was sent to a detention facility in Seattle. By the time they reunited, the pair had been apart for 58 days, Olivares said.

Mario, also from Guatemala, was accused of trafficking his own 2-year-old daughter, even though he had a birth certificate naming him as the father. The Guatemalan embassy authenticated the certificate, but the federal government would not release the daughter into her father’s custody until their blood relationship was determined by a DNA test. By the time this was verified, they had been separated for one month, said Olivares.

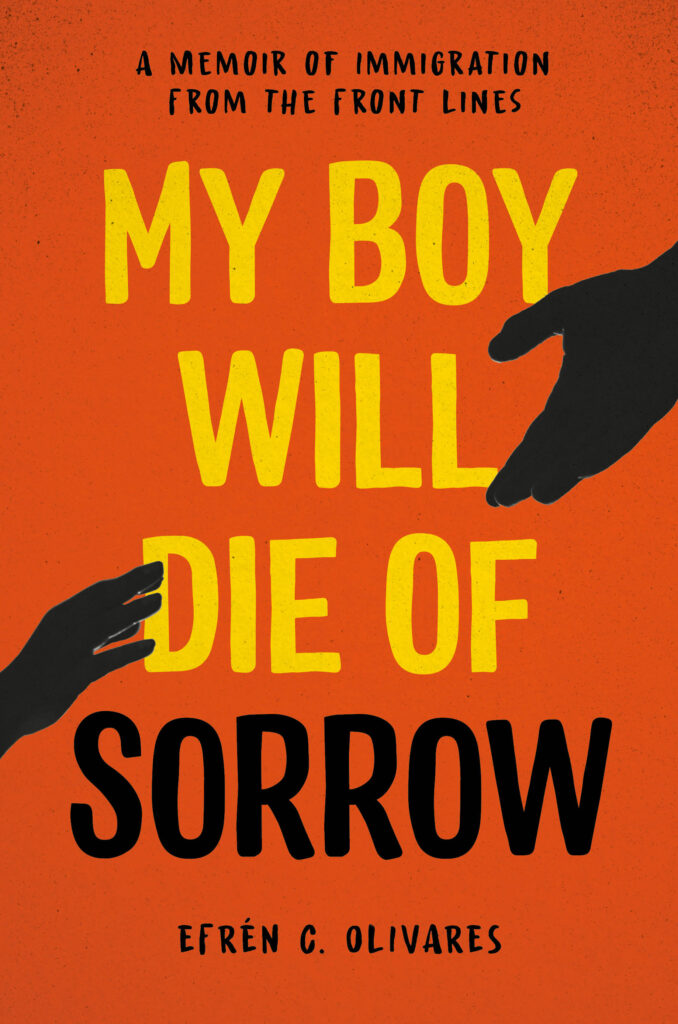

“I could tell you so many stories like that that I heard that summer,” Olivares said. He said he was struck by how easily this could have happened to him as a child. He had immigrated to the United States at 13. He later wrote a memoir, “My Boy Will Die of Sorrow,” speaking both to his work as a lawyer as well as his personal experience as an immigrant child.

The title, he said, came from a father that Olivares interviewed. When asked what he thought would happen if he were deported without being reunited with his son, the father said, “No, pues. Mi niño se muere de tristeza. My boy will die of sorrow,” Olivares said.

“Migrating is the most human thing that we do,” Olivares said. “For millennia, human beings have been moving across for two reasons: safety and opportunity.”

As the family separation aspect of the zero-tolerance policy came to light, Olivares kept hearing others say, “This is not who we are as a country. This is not the real United States. We’re a nation of immigrants. This is not us.”

“So I started looking into it,” he said. “Was this an anomaly?”

“Slavery,” Olivares said, was “the true precursor of the family separation policy.” Family separation among enslaved people was so commonplace that it was not uncommon to sell children away from their parents, he said.

Olivares said that the U.S. had a long history of restricting immigration based on country of origin, beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, moving to the Immigration Act in 1924, which was written to favor predominantly white Northern European countries.

The border patrol was founded that same year, with the specific intent of enforcing those quotas. “Families were separated in that process,” said Olivares. “This is nothing new.”

Still, the zero-tolerance policy was polemic, he said, with some Americans saying that family separation was justified because immigrants had committed a crime by crossing the border. But immigrants have been doing this for centuries, Olivares said, and some are refugees, who have a legal right to cross the border to ask for help.

“My colleagues and I would say, ‘Somebody’s got to have a conscience,’” Olivares said. “Somebody’s going to take a picture or a video from inside the facility, and even if it means risking their job somebody’s got to.

“We kept waiting and hoping for that, thinking that might be the thing that made a difference,” he said. Finally, an audio file was leaked to ProPublica, along with other news sources. The clip was eight minutes long, he said, and extremely painful. “Children, mostly little girls, inside of a detention center, crying for their mom and dad, crying for eight minutes nonstop.”

The audio file was leaked on a Monday evening, Olivares said. By Wednesday, the president signed an executive order stopping the family separation policy.

“That audio was so powerful in turning the public opinion against this policy,” said Olivares. “And I’m convinced that the reason that audio was so powerful—and much more powerful than a photo or a video would have been—is because when you hear the children cry, you don’t see the color of their skin. All children cry the same. You hear those little voices, you think of your own children, and it gets to you.”

The 2022 Dolores Huerta keynote lecture was hosted by the Albert M. Greenfield Intercultural Center and La Casa Latina and co-sponsored by the Center for Latinx and Latin American Studies, the Penn Carey Law School, the Association of Latino Alumni, the Center for the Study of Ethnicity, Race, and Immigration, the Huntsman Program of International Studies and Business, Penn First Plus Alumni, Penn Libraries Community Engagement Program, Penn Spectrum Programs, the Politics, Philosophy, and Economics Program, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Paideia Program, and The Office of Social Equity and Community.