As social psychologists, we are interested in understanding how such a toxic form of polarization manifests in our everyday psychology, and how the mental models we hold can undermine social cohesion and democratic health. And as concerned citizens who are also scientists, we are also interested in identifying evidence-based solutions to overcome the division that defines American politics. Through a partnership between a research team at the University of Pennsylvania and the nonprofit organization Beyond Conflict, we work to translate research on political polarization into science-backed interventions to reduce conflict.

Ideological division has been fused with an “us versus them” sectarianism that feels reminiscent of divisiveness and vitriol more commonly seen in war-torn countries than in healthy democracies.

In a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, our research team, led by Samantha Moore-Berg, found that Democrats and Republicans do disagree with and dislike each other (no big surprise there). Importantly, however, members of both parties overestimate the size of the partisan divide. This inaccuracy is a product of what psychologists call meta-perceptions—our perceptions of others’ attitudes and beliefs. The judgements that we make about how others view us or about what they believe can be very inaccurate, and the tendency to misperceive the beliefs of those who belong to a different political party than we do can have damaging consequences for democracy.

In one study, we surveyed more than 1,000 adults who were representative of the American public in terms of gender, age, race, and other key demographics. In our survey, participants who identified as Democrats and Republicans rated how much they liked Republicans and Democrats, respectively, as well as how evolved and how civilized they thought members of the other political party were (a measure of dehumanization). They then estimated how the average member of the other political party would answer the same question about their own group.

The tendency to misperceive the beliefs of those who belong to a different political party than we do can have damaging consequences for democracy.

We found that both Democrats and Republicans disliked and dehumanized the other party more than their own; however, both Democrats and Republicans estimated that the other group dehumanized and disliked their group about twice as much as in reality. In other words, both Democrats and Republicans greatly overestimated how much the other disliked and dehumanized them.

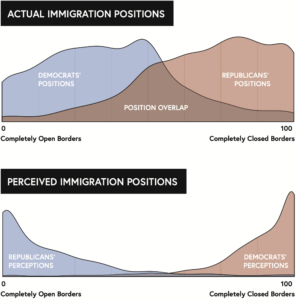

In the survey, respondents also indicated their policy preferences. For instance, they indicated whether they thought U.S. borders should be completely closed or completely open to all immigrants. Respondents answered using a sliding scale that ranged from 0 (completely closed) to 100 (completely open). Perhaps unsurprisingly, Republicans were more in favor of closed borders than Democrats (with average scores of 25 and 61, respectively). However, when asked to estimate how the other side would answer the same question, both Democrats and Republicans thought the divide was about twice as large. Again, members of each party overestimated their difference of opinion. As shown in the figure below, Democrats and Republicans had much more in common than they thought.

Why do these misperceptions matter?

Our attitudes and views toward each other aren’t static but are shaped by our perceptions of how others view us. Who would you be more willing to live next to, engage in difficult conversations with, or work with: someone who you think likes you and views you as human, or someone who you think hates you and views you as an animal because of your political beliefs? In this sense, what we think others think about us can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. When we assume that others hold views that are further apart from our own than they are in reality, we see little room for negotiation and have few reasons to work together.

In this same study, we found that the more Democrats and Republicans overestimated partisan divides, the more they also expressed a greater desire for social distance from members of their opposing party. For example, they said that they would be less comfortable visiting a doctor or having their child in a classroom taught by someone from the opposing political group. This desire for social distance—fueled by these inaccurate perceptions—can have cascading consequences. The more distant we are from each other, physically and psychologically, the less willing we are to get to know each other. And the less we know each other, the more inaccurate our perceptions of the other side will likely be.

When we assume that others hold views that are further apart from our own than they are in reality, we see little room for negotiation and have few reasons to work together.

These misperceptions can have even more sinister consequences. We also found that Democrats and Republicans who held more inaccurate beliefs about the other side were even willing to subvert norms of democracy to hurt their political opponents. Respondents were even willing to say that it was okay to sacrifice U.S. economic prosperity in the short term to hurt their opposing party, and that their own political party should engage in illegal gerrymandering to win more seats in federal elections. It goes without saying that this desire to harm members of our opposing political group undermines the very core of our democracy.

As bleak as the above results may seem, there is hope. Despite the prevailing narrative about how divided we are, we are not nearly as divided as we may think. Democrats and Republicans will certainly not agree on everything, but we do agree on more than we realize. That means that working together is possible if we are willing to look beyond our partisan identities.

We found that Democrats and Republicans who held more inaccurate beliefs about the other side were even willing to subvert norms of democracy to hurt their political opponents.

So, how can we depolarize our current political environment?

As outlined in a report published by Beyond Conflict, this research provides actionable ways to depolarize our political environment. First, we can help people to move beyond the echo-chambers that fuel our polarized understanding of each other and instead encourage people to learn more about the actual attitudes and views held by others. For example, programs like the One America Movement, which facilitates intentional conversations across divides, can help us correct the misperceptions that we have about our fellow citizens. Second, we can engage with leaders and the media who may be exacerbating Americans’ misperceptions of each other. In so doing, we can hopefully stop the spread of polarizing narratives that are driving a partisan wedge. And third, once we know that we have more in common than we first realized, we can more meaningfully engage with each other across the political spectrum. These approaches rest at the core of our approach to reduce partisan division.

We are on the heels of a historic election. Although President-Elect Biden has made explicit calls for unity, many Americans are wondering whether the next two to four years will be filled with partisan gridlock. We cannot predict what the future will hold. But we can say this—if Americans can be governed more by our shared beliefs than the inaccurate perceptions about the other side, there’s more room for progress than it may seem.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful for our collaborators Emile Bruneau, Boaz Hameiri, and Lee-Or Ankori-Karlinsky on this research.